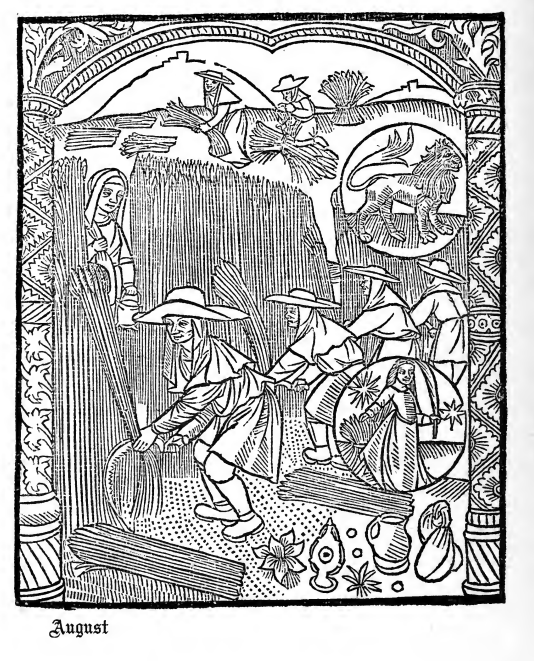

When I take Road Scholar groups to Chipping Campden, in the Cotswolds. We pass the Court House (pictured above) where I tell the story of the disappearance of William Harrison. Last time, looking at my old ragged notes, I noticed that the disappearance took place on the 16th August.

On that day in 1660 70 yr old William Harrison left the Court House where he was the Steward. The Steward went for a 2-mile walk, collecting rents. When he didn’t return, his wife sent out a man servant, John Perry, to bring him home. Neither had returned by the next morning.

Harrison’s son went out to search for his dad, and found John Perry. The two of them searched for Harrison without luck. Meanwhile, Harrison’s neckband and shirt were found with his hat. The clothes were said to be blood stained, but as those who read Sherlock Holmes will know, there was no certain test for blood stains (a test was introduced in the late 19th Century).

But the identification of blood stains led to suspicion of John Perry. He said he was innocent, but he buckled under questioning, maintaining it was nothing to do with him. B he claimed his brother and mother murdered Harrison for his money. Perry soon changed his testimony about his brother and mother and eventually pleaded insanity. All three were hanged.

Two years later, Harrison returned home, claiming to have been abducted by pirates and sold into slavery in Turkey before escaping and returning to England.

This is, pretty much, the bones of the story I have told my groups over the last 15 years. But what is wonderful about my job and this ‘Almanac of the Past:, is that you get to dig that little bit deeper than the local guidebook.

The first new ‘fact’ I discovered was that Harrison was Steward to the Lady Juliana Noel. She has a very prominent monument in St James Church, near the Court House and has long fascinated me. I will write more about her one day. Meanwhile, have a look at my post on her Dad, Baptist Hicks and how the family came to be Lords of the Manor of Chipping Campden, and Campden Hill, Notting Hill.

Back to my new discoveries about the Crime! John Perry, his mother and brother were actually tried twice for the crime. The first judge refused to try them for murder in the absence of the body. But they were encouraged to plead guilty to robbery, as they would then be eligible for an amnesty for first time convictions introduction by the new King Charles II on his restoration. So they were convicted.

However, another Judge was willing to try them in the absence of a body, and they were, after all, tried for the murder. But having pleaded guilty to robbery (to avoid the risk of being executed), they had no real defence to the charge and were sentenced to be hanged.

Nor was the hanging simple: Joan Perry, the mother, was hanged first because she was said to be a witch who was preventing her sons from pleading guilty. After she was hanged, her sons still maintained their innocence The oldest son was then hanged. But the youngest son still claimed his innocence and was hanged too.

The hangings took place on the hill above Broadway, the highest point of the Cotswolds, where Broadway Tower now stands, and a famous beauty spot. Mother and son were buried under the Gibbet, but John Perry was hanged in chains and kept on display as a warning to others not to follow his example.

As to William Harrison’s story of his abduction, it sounds a little unlikely in rural Gloucestershire. To a modern mind, it seems more likely that he felt the need to leave home, or had some form of breakdown, or did he collude with the Perry’s to steal money from the Noel Estate? I wonder how he reacted when told that three people lost their lives because of him?

But, it has been suggested that Harrison was kidnapped by people involved in the English Civil War who had secrets to keep which Harrison as Steward might have known. He said English people had kidnapped him and put on a ship to America which was attacked by ‘Turkish’ (maybe Barbary Pirates).

The case led to a ‘no body, no murder’ rule which survived until 1954. But in modern times a body is not essential to a successful prosecution for murder, particularly in domestic murder cases, provided there is sufficient evidence to prove the case.

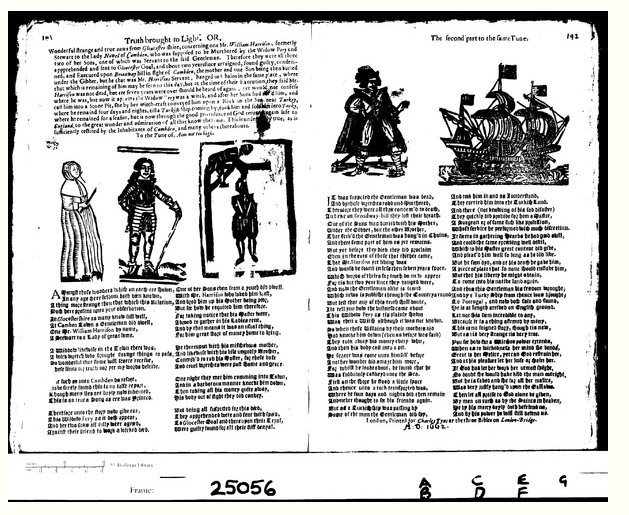

The case is normally referred to as ‘The Chipping Campden Wonder’ and it has often been written about, for example by Linda Stratmann. I have been wondering why it was so named, there being nothing wonderful about a murder or an abduction. But I have just found a ballad that was written about the case that might explain it. This claims that Joan Perry was indeed a witch, Harrison was attacked and buried in a pit but was, somehow, magically conveyed to Turkey, from which he eventually escaped to return to Chipping Campden. The Wonder is presumably the saving of Harrison and transportation to Turkey? The ballad clarifies that there was therefore no miscarriage of justice, as the Perrys were involved with diabolical doings, and that the Grace of God saved Harrison despite the best efforts of the Perrys.

Well worth reading the text of the ballad below (source: https://omeka.cloud.unimelb.edu.au/execution-ballads/items/show/1216)

Bodleian 18713, Wood 401(191), Bod18713

‘Amongst those wonders which on early are shown,

In any age there seldom hath béen known,

A thing more strange then that which this Relation,

Doth here present unto your observation.

In Glocestershire as many know full well,

At Camben Town a Gentleman did dwell,

One Mr. William Harrison by name,

A Stewart to a Lady of great fame.

A Widdow likewise in the Town there was,

A wick wretch who brought strange things to pass,

So wonderful that some will scarce receive,

[…]hese lines for truth nor yet my words beleive.

[…] such as unto Cambden do resort,

Have surely found this is no false report,

Though many lies are dayly now invented,

This is as true a Song as ere was Printed.

Therefore unto the story now give ear,

This Widow Pery as it doth appear,

And her two sons all fully were agréed,

Against their friend to work a wicked déed.

One of her Sons even from a youth did dwell,

With Mr. Harrison who loved him well,

And bred him up his Mother being poor,

But sée how he requited him therefore.

For taking notice that his Master went,

Abroad to gather in his Ladies rent,

And by that means it was an usual thing,

For him great store of money home to bring.

He thereupon with his mischevous mother,

And likewise with his vile ungodly Brother,

Contriv’d to rob his Master, for these base

And cruel wretches were past shame and grace.

One night they met him comming into Town,

And in a barbarous manner knockt him down,

Then taking all his money quite away,

His body out of sight they did convey.

But being all suspected for this déed,

They apprehended were and sent with spéed,

To Glocester Goal and there upon their Tryal,

Were guilty found for all their stiff denyal.

Jt was supposed the Gentleman was dead,

And by these wretches robd and Murthered,

Therefore they were all thrée condem’d to death,

And eke on Broadway-hill they lost their breath.

One of the Sons was buried with his Mother,

Vnder the Gibbet, but the other Brother,

That serv’d the Gentleman was hang’d in Chains,

And there some part of him as yet remains.

But yet before they died they did proclaim

Even in the ears of those that thither came,

That Mr. Harison yet living was

And would be found in less then seven years space.

Which words of theirs for truth do now appear

For tis but two year since they hanged were,

And now the Gentleman alive is found

Which news is publisht through the Countrys round

But lest that any of this truth shall doubt,

Ile tell you how the business came about

This Widow Pery as tis plainly shown

Was then a Witch although it was not known.

So when these Villains by their mothers aid

Had knockt him down (even as before was said)

They took away his money every whit,

And then his body cast into a pit.

He scarce was come unto himself before

Another wonder did amaze him more,

For whilst he lookt about, he found that he

Was suddainly conveyd unto the Sea.

First on the shore he stood a little space

And thence unto a rock transported was,

Where he four days and nights did then remain

And never thought to see his friends again.

But as a Turkish ship was passing by

Some of the men the Gentleman did spy,

And took him in and as I understand,

They carried him into the Turkish Land.

And there (not knowing of his sad disaster)

They quickly did provide for him a Master,

A Surgeon or of some such like profession,

Whose service he performed with much discretion.

It séems in gathering Hearbs he had good skill,

And could the same excéeding well distil,

Which to his Master great content did give,

And pleas’d him well so long as he did live.

But he soon dyd, and at his death he gave him,

A piece of plate that so none should enslave him,

But that his liberty be might obtain,

To come into his native land again.

And thus this Gentleman his fréedom wrought;

And by a Turky Ship from thence was brought;

To Portugal, and now both safe and sound,

He is at length arrived on English ground.

Let not this séem incredible to any,

Because it is a thing afirmed by many,

This is no feigned story, though tis new,

But as tis very strange tis very true.

You sée how far a Witches power extends,

When as to wickedness her mind she bends,

Great is her Malice, yet can God restrain her,

And at his pleasure let her loose or chain her.

If God had let her work her utmost spight,

No doubt she would have kild the man outright,

But he is saved and she for all her malice,

Was very justly hang’d upon the Gallows.

Then let all praise to God alone be given,

By men on earth as by the Saints in heaven,

He by his mercy dayly doth befriend us,

And by his power he will still defend us.’

Set to tune of ‘Aim Not Too High (Fortune My Foe)’

This was transcribed on this site, which is well worth a look!

https://omeka.cloud.unimelb.edu.au/execution-ballads/items/show/1216

First published 2024, republished August 2025