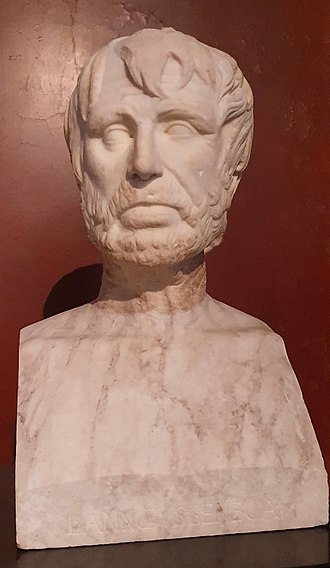

Hesiod is a contemporary of Homer, and therefore one of the first European poets, one of the first commentators on Greek life, thought, religion, mythology, farming and time keeping. ‘Works and Days’ is his Farmers Almanac and therefore long overdue an appearance on my Almanac of the Past.

Hesiod’s poems also introduce the idea of the epoch, past glorious epochs of Gold and Bronze with a further descent to his own epoch which was of the base metal age of Iron. In the 19th Century, European antiquarians, imbued with a humanist belief in Progress, developed the idea of Stone, Bronze and Iron Ages, an almost direct opposite of Hesiod’s, downhill-all-the-way to the present idea.

Hesiod also brings in early references to Prometheus and Pandora, two of the great myths of the flaws of humanity.

This is what he says of Winter. It is from a translation by Christopher Kelk, available to download here (I have added line breaks after full stops, just for ease of reading.)

…. you should make

A detour during winter when the cold

Keeps men from work, for then a busy man

May serve his house. Let hardship not take hold,

Nor helplessness, through cruel winter’s span,

Nor rub your swollen foot with scrawny hand.An idle man will often, while in vain

He hopes, lacking a living from his land,

Consider crime. A needy man will gain

Nothing from hope while sitting in the street

And gossiping, no livelihood in sight.Say to your slaves in the midsummer heat:

“There won’t always be summer, shining bright –

Build barns.” Lenaion’s evil days, which gall

The oxen, guard yourself against. Beware

Of hoar-frosts, too, which bring distress to all

When the North Wind blows, which blasts upon the air

In horse-rich Thrace and rouses the broad sea,

Making the earth and woods resound with wails.He falls on many a lofty-leafed oak-tree

And on thick pines along the mountain-vales

And fecund earth, the vast woods bellowing.

The wild beasts, tails between their legs, all shake.Although their shaggy hair is covering

Their hides, yet still the cold will always make

Their way straight through the hairiest beast.Straight through

An ox’s hide the North Wind blows and drills

Through long-haired goats. His strength, though, cannot do

Great harm to sheep who keep away all chills

With ample fleece. He makes old men stoop low

But soft-skinned maids he never will go through –

They stay indoors, who as yet do not know

Gold Aphrodite’s work, a comfort to

Their darling mothers, and their tender skin

They wash and smear with oil in winter’s space

And slumber in a bedroom far within

The house, when in his cold and dreadful place

The Boneless gnaws his foot (the sun won’t show

Him pastures but rotate around the land

Of black men and for all the Greeks is slow

To brighten).That’s the time the hornèd and

The unhorned beasts of the wood flee to the brush,

Teeth all a-chatter, with one thought in mind –

To find some thick-packed shelter, p’raps a bush

Or hollow rock. Like one with head inclined

Towards the ground, spine shattered, with a stick

To hold him up, they wander as they try

To circumvent the snow.As I ordain,

Shelter your body, too, when snow is nigh –

A fleecy coat and, reaching to the floor,

A tunic. Both the warp and woof must you

Entwine but of the woof there must be more

Than of the warp. Don this, for, if you do,

Your hair stays still, not shaking everywhere.Be stoutly shod with ox-hide boots which you

Must line with felt. In winter have a care

To sew two young kids’ hides to the sinew

Of an ox to keep the downpour from your back,

A knit cap for your head to keep your ears

From getting wet.It’s freezing at the crack

Of dawn, which from the starry sky appears

When Boreas drops down: then is there spread

A fruitful mist upon the land which falls

Upon the blessed fields and which is fed

By endless rivers, raised on high by squalls.Sometimes it rains at evening, then again,

When the thickly-compressed clouds are animated

By Thracian Boreas, it blows hard. Then

It is the time, having anticipated

All this, to finish and go home lest you

Should be enwrapped by some dark cloud, heaven-sent,

Your flesh all wet, your clothing drenched right through.This is the harshest month, both violent

And harsh to beast and man – so you have need

To be alert. Give to your men more fare

Than usual but halve your oxen’s feed.

The helpful nights are long, and so take care.Keep at this till the year’s end when the days

And nights are equal and a diverse cropKeep at this till the year’s end when the days

Hesiod’s Works and Days: Translation Christopher Kelk

And nights are equal and a diverse crop

Springs from our mother earth and winter’s phase

Is two months old and from pure Ocean’s top

Arcturus rises, shining, at twilight.

Acturus is not seen in winter, and in the Northern Hemisphere its rising (50 days after the winter solstice) and has always been associated with the advent of spring.

Boreas was the winged God of the North wind, which bore down from the cold Mountains of Thrace (north of Macedonia). One of his daughters, Khione, was the Goddess of Snow. Lenaion was associated with January one of the festivals of Dionysus, and a theatrical season in Athens particularly for comedy.

First published 15th December 2022, republished December 2023, 2024

‘Les très riches heures du duc de Berry’, a prayer book, also offers a very lively picture of life through the seasons in late Middle Ages with its beautiful illuminations.

yes, its a very beautiful book – I use it a lot in my lectures, and virtual tours on the medieval period and on Chaucer, and will probably feature it here, if I’m sure of copyright issues.