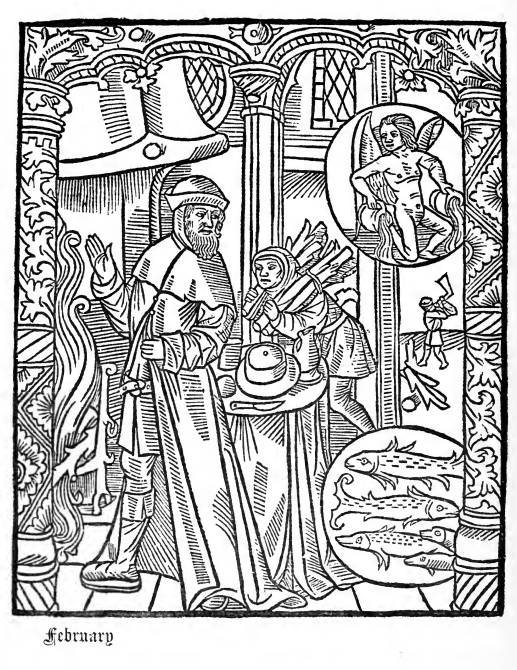

Candlemas is an important festival of the Church, celebrated throughout the Christian world. It is the day Jesus was presented to the Temple as a young boy and prophesied to be ‘a light to lighten the Gentiles’. The day is therefore celebrated by lighting candles. Hence its name.

It is also called the Feast of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary. It is 40 days after the birth of Jesus which was fixed as the 25th December by Pope Liberius by AD 354. So it is the end of the postpartum period ‘as the mother’s body, including hormone levels and uterus size, returns to a non-pregnant state’. Mary went to the Temple to be ritually cleansed. This later became known as ‘churching’.

Candlemas a Cross Quarter Day.

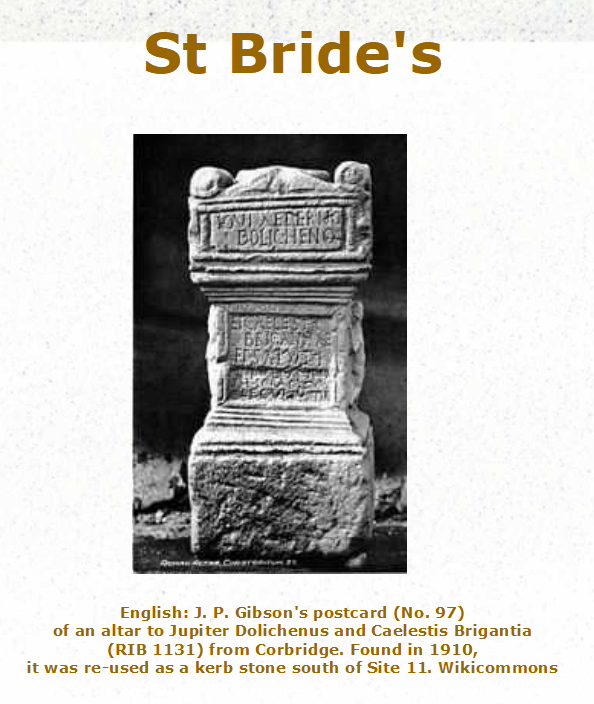

It is also one of the cross quarter days of the Celtic tradition, that is halfway between Winter Solstice and May Day. The candles also suggest a light festival marking the lengthening days. It is probably another of those festivals where the Christian Church has taken on aspects of the pagan rituals, so Brigantia’s (celebrated at Imbolc on February 1st) role in fertility is aligned with the Virgin Mary’s.

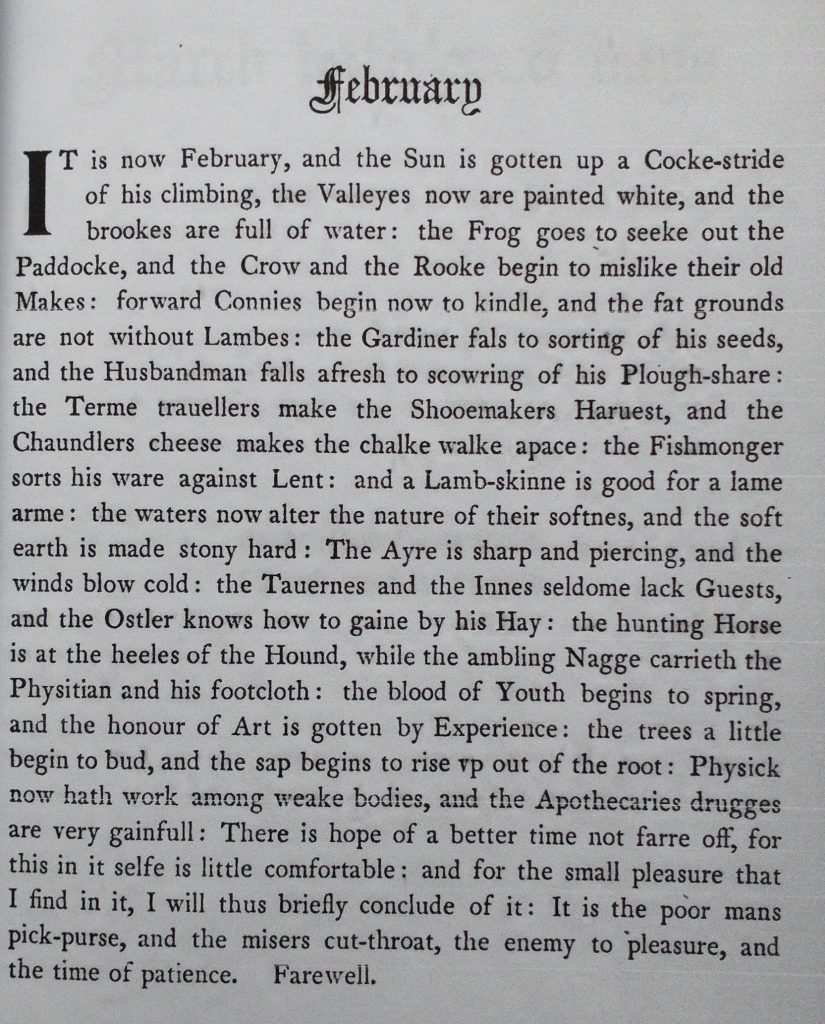

Weather Lore for Candlemas

Folklore prophecies for today: ‘If it is cold and icy, the worst of the winter is over, if it is clear and fine, the worst of the winter is to come.’ Looking overhead I can see a little blue sky but I can’t say it is ‘clear and fine’. But it is certainly not ‘cold and icy’. So, for what it is worth, we are in for some cold weather.

Candlemas – the Last day of medieval Christmas and the Lords of Misrule.

It’s also the official end of all things Christmas. For most of us Christmas decorations were supposed to be pulled down on January 5th, but, the Church itself puts an end to Christmas officially at Candlemas so Cribs and Nativity tableaux need to be removed today.

John Stow, in the 16th Century describes the period between Halloween and Candlemas as the time when London was ruled by various Lords of Misrule and Boy Bishops (see my post here). In the piece below, Stow also talks about a terrible storm that took place in February 1444.

Against the feast of Christmas every man’s house, as also the parish churches, were decked with holm, ivy, bays, and whatsoever the season of the year afforded to be green. The conduits and standards in the streets were likewise garnished; amongst the which I read, in the year 1444, that by tempest of thunder and lightning, on the 1st of February, at night, Powle’s steeple was fired, but with great labour quenched; and towards the morning of Candlemas day, at the Leaden hall in Cornhill, a standard of tree being set up in midst of the pavement, fast in the ground, nailed full of holm and ivy, for disport of Christmas to the people, was torn up, and cast down by the malignant spirit (as was thought), and the stones of the pavement all about were cast in the streets, and into divers houses, so that the people were sore aghast of the great tempests.’

Robert Herrick has a 17th Century poem about Candlemas:

Ceremony Upon Candlemas Eve

Down with the rosemary, and so

https://www.catholicculture.org

Down with the bays and misletoe;

Down with the holly, ivy, all

Wherewith ye dress’d the Christmas hall;

That so the superstitious find

No one least branch there left behind;

For look, how many leaves there be

Neglected there, maids, trust to me,

So many goblins you shall see.

On This Day

1602 – Twelfth Night by William Shakespeare performed for the first time.

This play was commissioned by the Lawyers of Middle Temple, in Fleet Street London for the end of the Christmas Season. It was written by Shakespeare and first performed in Middle Temple Hall which is still standing. For the folklore of Twelfth Night see my post here.

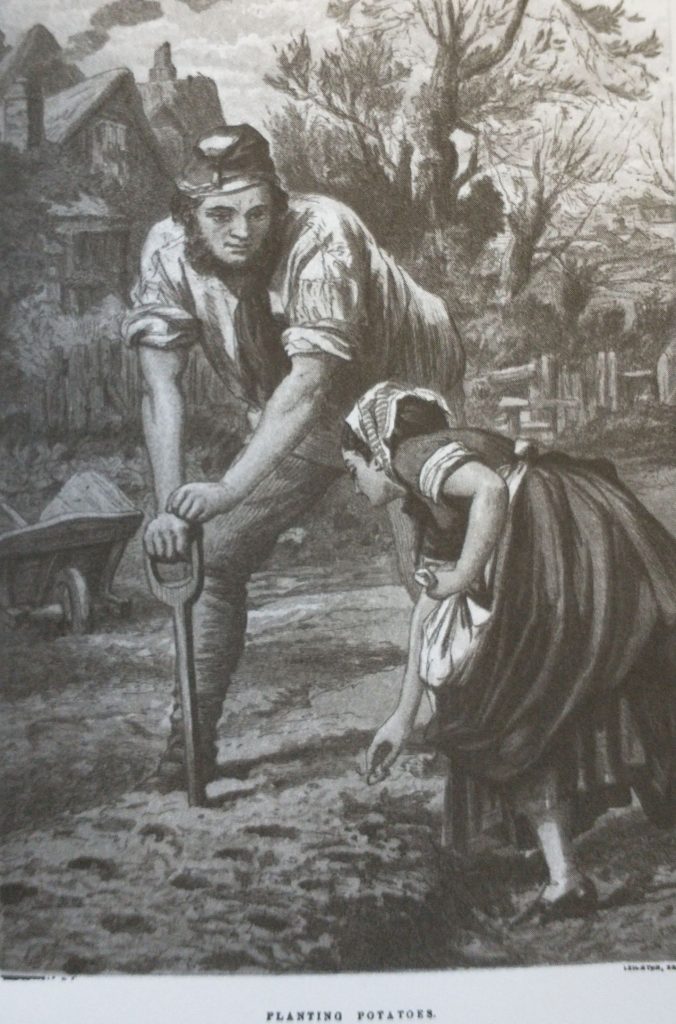

1880 – First shipment of frozen meat arrives in London from Australia. It was in excellent condition despite a leaving Melbourne in Dec 1879. Hay’s Gallerie in London was one of the world’s first warehouses with refrigeration.

1943 – German Army surrenders ending the Battle of Stalingrad, marking the beginning of the end of the WW2.

Today is Groundhog Day in the USA. This is when the groundhog comes out to see what the weather is like. If it is dull and wet he stays up because winter will be soon over, if it is sunny and bright he goes back to his burrow to hibernate for another 6 weeks. Originally, a German custom associated with the badger. A groundhog is a woodchuck which is a marmot. Does this workas a forecast method? Not being in America I don’t know but what I do know is:

How much wood could a woodchuck chuck

If a woodchuck could chuck wood?

As much wood as a woodchuck could chuck,

If a woodchuck could chuck wood.

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/42904/how-much-wood-could-a-woodchuck-chuck-

First published 2022, revised 2023, 2024, 2025 On This day added February 2026