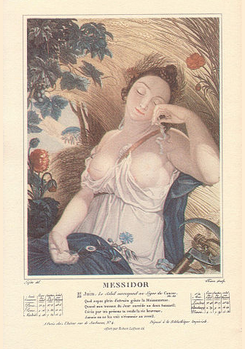

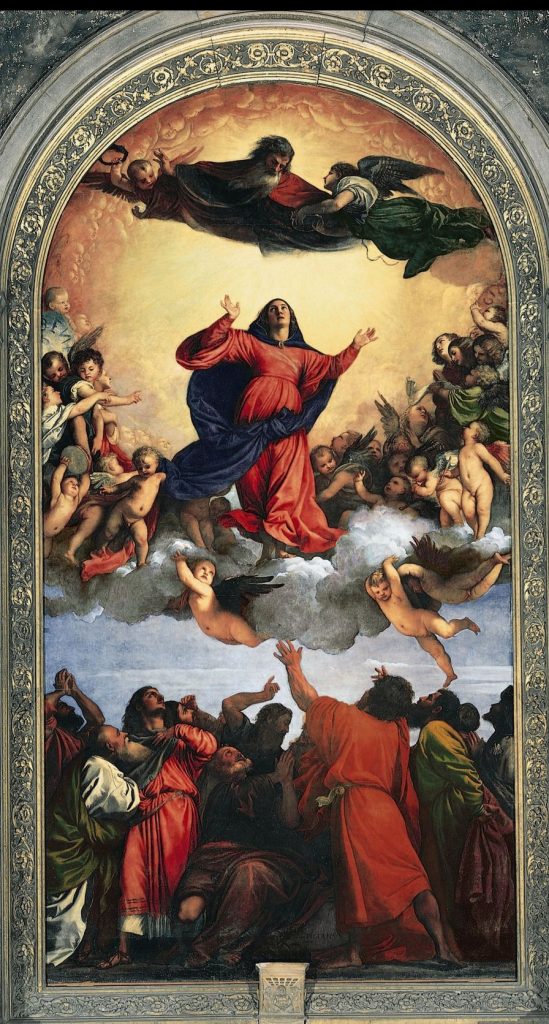

August 15th is the date of the celebration of the Assumption of St Mary. This is the day she went to heaven. Opinion is divided as to whether she died and went straight to heaven. Or did she go directly to heaven without having to pass go? The stories about the Virgin Mary were a big part of the controversy in the Reformation. Protestants did not find evidence in the Bible supporting many of the tales they had been told by the clergy. Once they could read the Bible in their own language they were able to assess the evidence for themselves.

August 15th was taken as a day off in the Medieval oeriod. My post is inspired by Octavia Randolph who has an excellent web site with a fine post on Anglo Saxon Slavery. You can read the post here: https://octavia.net/slavery-in-anglo-saxon-england. But what particularly caught my attention was the excerpt from King Alfred the Great’s laws. It lays down the law on the days off which should be given to freemen.

‘These days are to be given to all free men, but not to slaves and unfree labourers: twelve days at Christmas; and the day on which Christ overcame the devil (15 February); and the anniversary of St Gregory (12 March); and the seven days before Easter and the seven after; and one day at the feast of St Peter and St Paul (29 June); and in harvest-time the whole week before the feast of St Mary (15 August); and one day at the feast of All Saints (1 November). And the four Wednesdays in the four Ember weeks are to be given to all slaves, to sell to whomsoever they please anything of what anyone has given them in God’s name, or of what they can earn in any of their spare time.

Translated by Simon Keynes and Michael Lapidge and taken from Octavia.net

That comes to 38 days by my reckoning. In the UK 4 weeks off is a good average holiday entitlement. If we add 8 bank holidays in England and Wales that gives us 36 days off a year. So 1500 years of ‘progress’ has given us minus 2 days, and a lot less in the USA!

How depressing! Of course, most of these days off were lost during the Industrial Revolution and only clawed back by Trade Unions.

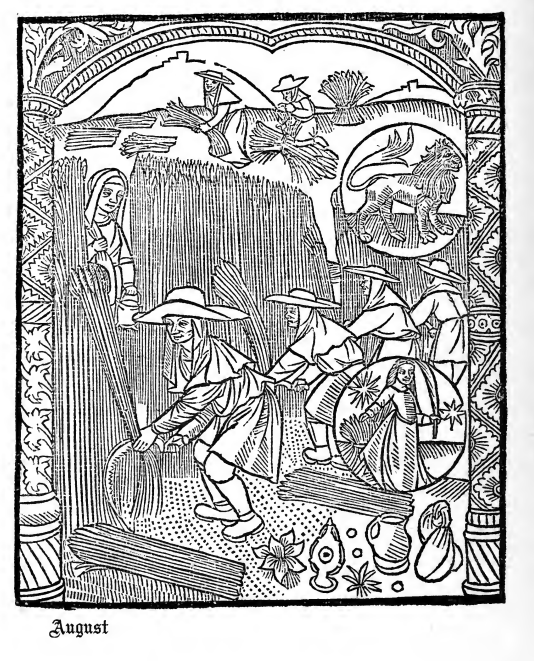

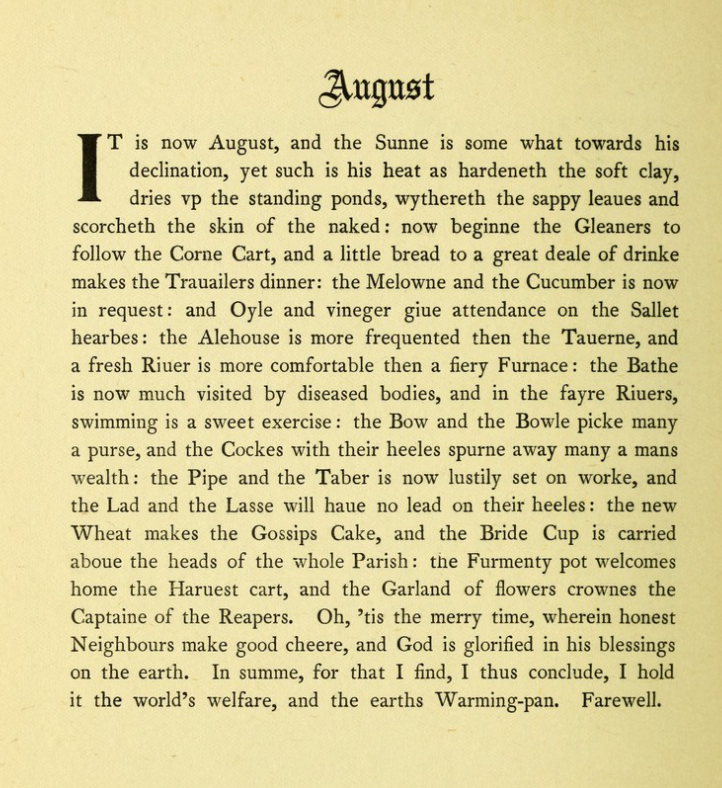

The days off are interesting, obviously Christmas and Easter. Harvest is more of a surprise in that one would expect to be working very hard bringing in the harvest. But, maybe the 7 days off were given after it was brought in?

The individual days make sense as they are the feasts of major saints or festivals – so St Gregory’s Day – he being the Pope who ordered the mission to convert the English to Christianity in 597AD. (See my post on St Gregory here).

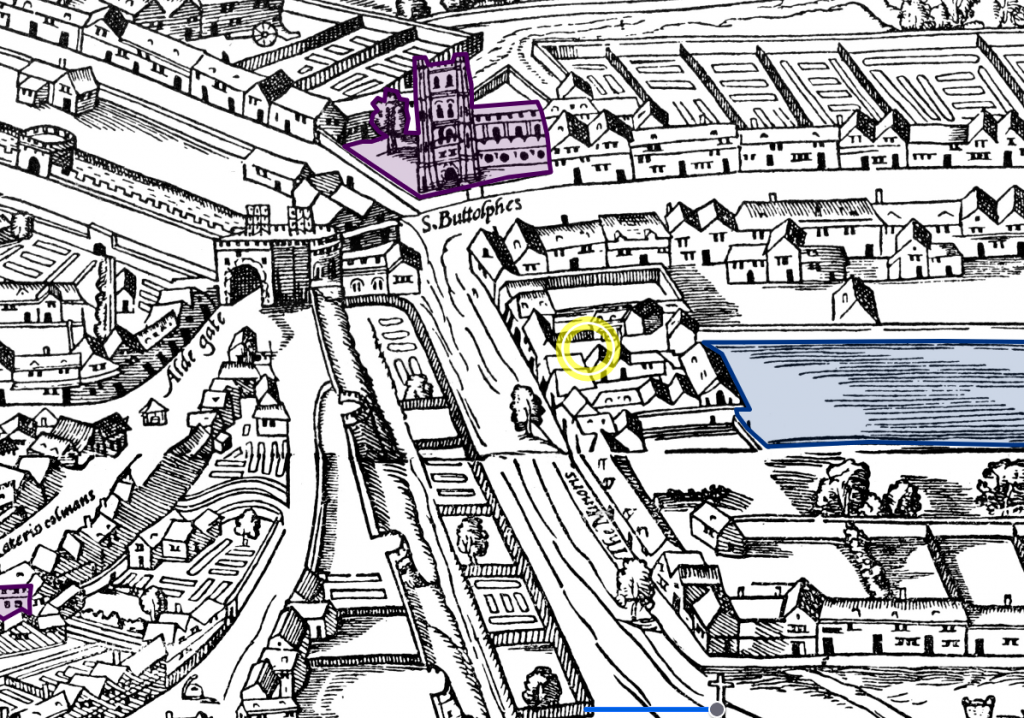

Saints Peter and Pauls Day. St Mary and All Saints Day. I’m surprised there is no Candlemas or Michelmas.(More information about celebration of St Peter and St Paul in London in my post here)

Slaves holidays

Slaves seem to only have 4 days however. These are the Wednesday in Ember Weeks. Ember Days and Ember Weeks were Fasting Days, either named after a latin phrase for fasting or from Ymbren which is the Anglo-Saxon for circuit or revolution. It is thought that the days were originally tied to the ‘cycle of life’ that it part of each year. But later on became more liturgical and based on fasting.

They may have been founded in Roman roots. There only seems to be 3 in the days of the early church, rising to 4 ember weeks by the late 5th Century. They were brought to Britain by the mission of St Augustine, under Pope Gregory. These seem to be the dates:

December the week starting after St Lucy’s Day (Dec 13th)

March between 1st and 2nd Sunday

June between Pentecost and Trinity Sunday

September 3rd Week ending at Michaelmas.

So, the poor old slaves get 4 Wednesdays off in the year! This is presumably because the work of the household continues throughout the year, irrespective of season or festival. Maybe they are given a day off on the fasting days because household work can be put off as everyone is fasting?

But the laws make it clear: this is the time the poor slaves can work for themselves and make a little on the side.

Do have a look at Octavia’s web site which for more on slaves in the Anglo-Saxon period.

First published in August 2025