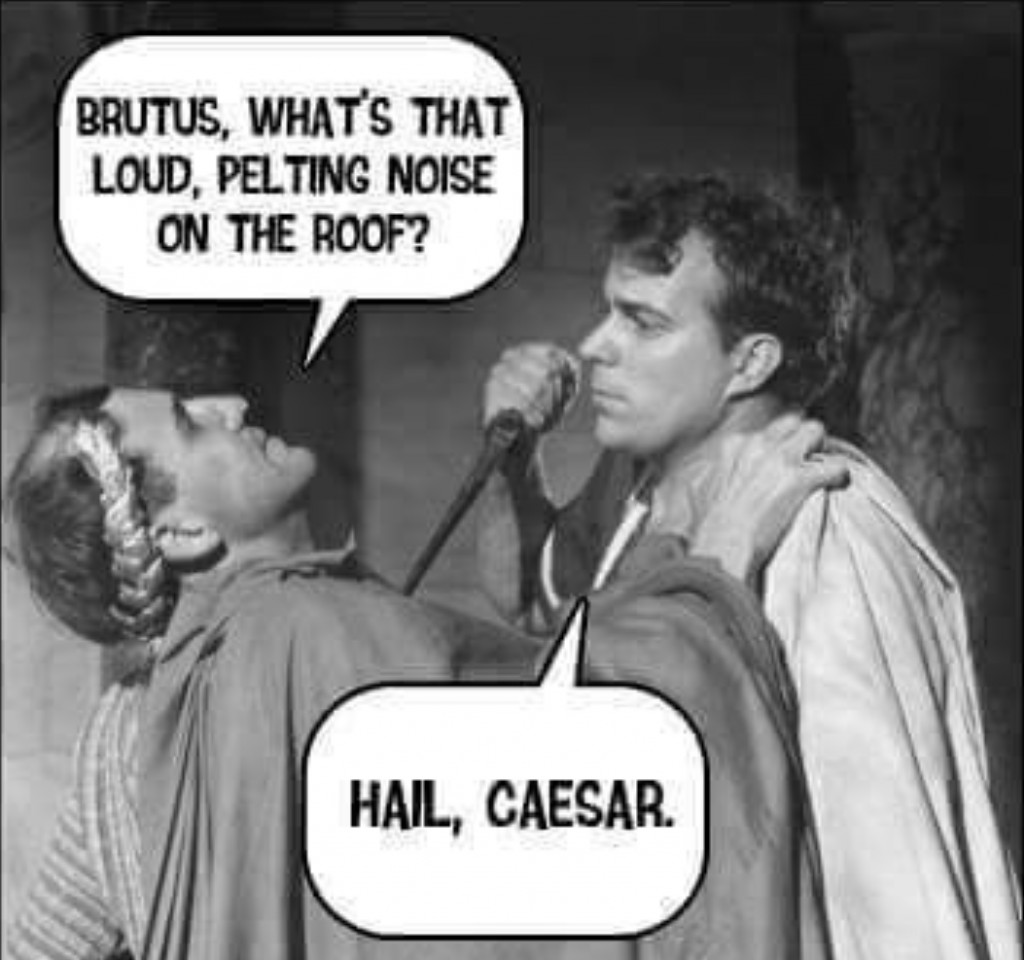

SOOTHSAYER: Caesar!

CAESAR: Ha! Who calls?

CASCA: Bid every noise be still; peace yet again!

CAESAR: Who is it in the press that calls on me?

I hear a tongue shriller than all the music

Cry ‘ Caesar!’ Speak. Caesar is turned to hear.

SOOTHSAYER: Beware the ides of March.

CAESAR: What man is that?

BRUTUS: A soothsayer bids you beware the ides of March.

CAESAR: Set him before me; let me see his face.

CASSIUS: Fellow, come from the throng; look upon Caesar.

CAESAR: What sayst thou to me now? Speak once again.

SOOTHSAYER: Beware the Ides of March.

CAESAR: He is a dreamer. Let us leave him. Pass.

Julius Caesar by William Shakespeare

Julius Caesar and the Ides of March

The Ides of March is the 15th of March. Julius Caesar didn’t take the warning that might have saved his life. You might suggest he got what was coming to first populist. But any study of Roman History will find many precursors in Roman and Greek History. Among populists, I rank Caesar with Napoleon as one of the Dictators who was, personally, an intelligent, reasonable man. They, in some ways, ruled ‘wisely’ but were nonetheless willing to sacrifice millions of people for their own personal ambition.

Today, the world is faced with the populists who are geniuses only in their own minds. I know, we as humans, might think, if only X would drop dead, how much better it would be? Brutus, being an honourable man, took action upon his thought. But, as often is the case, what seemed the ‘right thing’ to do, turned out to be a disaster. The plotters were trying to save the Roman Republic, but their murder destroyed the Republic. So, still those assassinary thoughts, read this article in ‘History Today’ about the impact of Julius Caesar’s murder. Do everything you can but use democratic means to defeat egotists to whom truth means nothing. In my opinion this is the major problem for humanity, it seems we do not know how to stop homicidal maniacs causing war without needing to fight a war to stop them. We do not have a method of peaceful mass rebellion. Perhaps Gandhi came closest but then he was working against a system that was not a dictatorship.

Ides of March

Now, what the heck are or indeed is the Ides of March?

A Roman month was divided into three, first the Kalends, then the Nones and finally the Ides. These three days were the important days of the month. The Kalends is the 1st of the Month. The Nones the 7th of the Month, And the Ides the Fifteenth. It is said to go back to the early days of Rome and a lunar calendar. The Kalends being the first tiny sliver of a crescent moon a couple of days after the New Moon. The Nones the first quarter of the Moon and the Ides was the full moon. To me, as a way of dividing a month it is very lopsided. The cycle of the moon is 29 days not 15. So the tripartite division divides up the first half of the month, and leave the second half undivided.

Debts were supposed to be paid on the Kalends and that is where we get our word calendar from. These public calendars were called Fasti. This is the name of Ovid’s great Almanac Poem, the Fasti, which I often quote from.

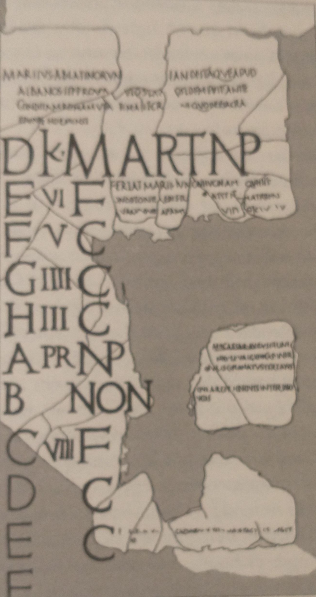

How was it used? When talking about a day in the future month you might say I’ll meet you on the 5th day before the Kalends. I’ve never really understood this system, despite a few attempts, until I saw this drawing of a Roman Calendar. You’ll have to read this closely. The first column, on the left, with the letters from D to H then A – H. This is a recurring cycle of 8 market days, running in tandem with Kalends, Nones etc.. This gives an 8 day week.

Now reading across the top line DKMARTNP. So the D is the 4 day of the 8 day ‘market week’. The second column begins with the Letter K for Kalends, then MART for March. So it’s the Kalends of March. Then NP which means this day is a day for public festivals.

Back to the second column. Below the K for Kalends, the days are counted down to the upcoming Nones. So the next one after Kalends is VI, meaning the 6th day before the March Nones. Then V, IIII, III. There is no II because PR means the day before Nones. Below and to the right of the PR are the letters NON which is, as you might hope, is short for Nones.

In the second column below this is the number VIII which means the next day is the 8th day before the Ides of March. The fragment of stone from which this drawing comes does not continue down to the Ides, unfortunately.

Complicated, huh? It gets worse. The third column has a series of letters in it: F C C C NP NON F C C. We already know that the NON is short for Nones, The F means it’s a fastus, a permissible day when legal action can be taken. (the plural of Fastus is Fasti.) The C means C comitialis which on fasti days the Roman people could hold assemblies. (see my post for more on the curiae). We have already seen that NP marks days for public festivals. An N would mean days when political and judicial actions were prohibited, although there is not one here. The small unreadable text to the right is information, I believe, about holidays and historic events to be marked in the calendar. This is, in fact, a Roman Stone Almanac.

This confusing system survived Caesar’s major calendrical reforms. He transformed the Roman calendar, which was rotten at the core. He re-aligned with an almost accurate calculation of the time the Sun takes to circle the earth. (or the other way around!) This is known as the Julian Calendar.

But the Kalends, Nones, and Ides he left intact until Constantine the Great got rid of them. They were replaced with the familiar 4 fold division of the month. So, for the first time, you could work 24/7.

For more about Constantine’s Weeks look at my post here

For Caesar’s Calendrical reforms look at this post

2024 Revised March 2025