Sementivae, was a festival dedicated to seed and to Ceres. Ceres is the Corn Goddess who gives her name to our word cereal. The festival was also called. Paganalia. The Mediterranean world had many names for the Earth Goddess. Tellus, Demeter, Cybele, Gaia, Rhea etc. who is celebrated around this time of the year with Ceres.

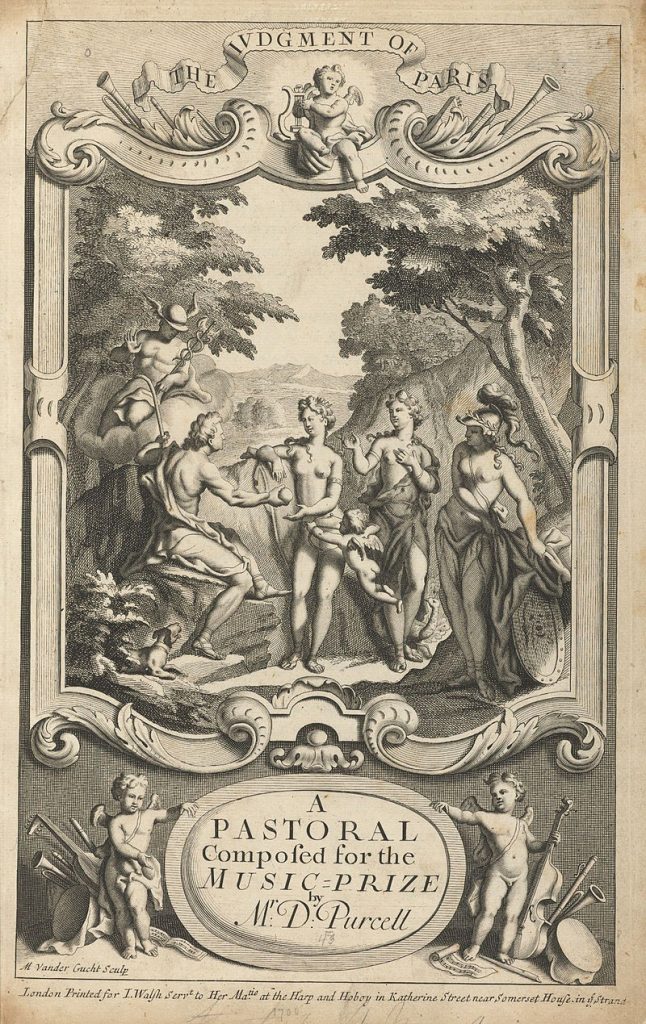

Ceres can be seen on the top left roundel resting on the Globe on the marvellous Ceramic Staircase at the V&A (photo above). And in my slightly out of focus photograph below. (To be honest, in real life, it looks a little more like my photo than the gorgeous photo above!)

Sementivae Dies – a moveable feast.

To create life, we need earth and water to nurture and seeds for their fertility. And so into the cold dead world of January the Romans created a festival of sowing. It had two parts, one presided over by Mother Earth (Tellus) and the other by Ceres, the Goddess of Corn. The actual day of the festival was chosen not by rote on a set day of the calendar but by the priests, in accordance with the weather. This seems very sensible, as there is no point sowing seeds in terrible weather conditions. I’m assuming the Priests took professional advice!

On the 24th-26th January Tellus prepared the soil, and in early February seeds were sown under the aegis of Ceres. Tellus Mater (also Terra Mater) was known as Gaia to the Greeks.

Gaia

Gaia was selected by James Lovelock & Lynn Margulis in the 1970s as the face of their Gaia hypothesis. To me, the importance of the idea is not the scientific principle that environments co-evolve with the organisms within them. But, rather in Gaia as a personification of our world as a complex living ecosystem. One that we have to care for. Gaia exists as a series of feedback loops. Lovelock hypotheses is that she will spit us out unless we can live in balance with our alma mater. I cannot believe he was not knighted. However, he is one of my heros.

Here is a tribute to Lovelock by his friend Bryan Appleyard. In it. He claims that work done by Lovelock ‘saved the world’. Lovelock invented a device that enabled the detection (and eventual eradication) of DDT and CFCs. If you remember, CFCs were destroying the Ozone layer until international agreement phased them out. Lovelock also worked for MI5. Appleyard, writing in The Sunday Times, described Lovelock as “basically Q in the James Bond films”.

Ovid and Sementivae

Ovid allocated January 24th to Sementivae but explains it is a variable date. But let’s let the Roman Poet Ovid has to say in his poetic Almanac known as ‘Fasti’ (www.poetryintranslation.com)

Book I: January 24

I have searched the calendar three or four times,

But nowhere found the Day of Sowing:

Seeing this, the Muse said: That day is set by the priests,

Why are you looking for moveable days in the calendar?

Though the day of the feast ís uncertain, its time is known,

When the seed has been sown and the land ís productive.

You bullocks, crowned with garlands, stand at the full

trough,

Your labour will return with the warmth of spring.

Let the farmer hang the toil-worn plough on its post:

The wintry earth dreaded its every wound.

Steward, let the soil rest when the sowing is done,

And let the men who worked the soil rest too.

Let the village keep festival: farmers, purify the village,

And offer the yearly cakes on the village hearths.

Propitiate Earth and Ceres, the mothers of the crops,

With their own corn, and a pregnant sow ís entrails.

Ceres and Earth fulfil a common function:

One supplies the chance to bear, the other the soil.

Partners in toil, you who improved on ancient days

Replacing acorns with more useful foods,

Satisfy the eager farmers with full harvest,

So they reap a worthy prize from their efforts.

Grant the tender seeds perpetual fruitfulness,

Don’t let new shoots be scorched by cold snows.

When we sow, let the sky be clear with calm breezes,

Sprinkle the buried seed with heavenly rain.

Forbid the birds, that prey on cultivated land,

To ruin the cornfields in destructive crowds.

You too, spare the sown seed, you ants,

So you’ll win a greater prize from the harvest.

For more on Ovid look at my post on Ovid and Juno here. Or you can search for Ovid in the Search box for other my posts on the Roman poet.

On This Day

1788 – Foundation of the first colony of European Settlers at Port Jackson, now Sydney. It is now Australia Day, a public holiday.

1841 – Hong Kong became a British Sovereign Territory

1926 – The first Public demonstration of a TV image given by Scottish electrical engineer John Logie Baird (1888-1946)

1998 – ‘I did not have sexual relations with that woman’ or so said Bill Clinton, lying through his teeth. (although I guess it depends on your definition of lying?) For more, look at the Time article here.

First Published in January 2023, republished in January 2024, 2025, 2026