St. Swithun’s day if thou dost rain

For forty days it will remain

St. Swithun’s day if thou be fair

For forty days ’twill rain nae mare

It’s not just important for the farmer but, even more, for the corn factor, to get the weather right for harvest. So, this bit of weather lore, repeated every year in the media could be important. But the BBC tells us that, since records have been kept (1841) there has been no period of 40 days rain after St Swithins Day. St Swithin was Bishop of Winchesterwho died in the early 9th Century AD.

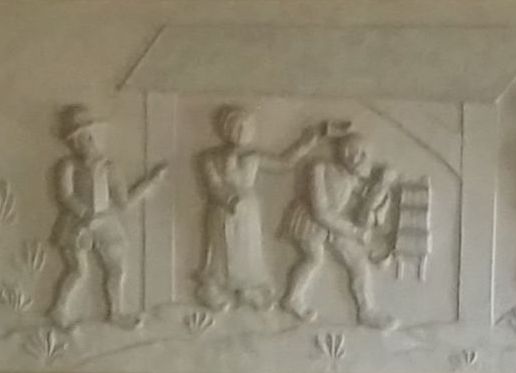

The price of corn is very dependent upon the weather. Michael Henchard in Thomas Hardy’s 1886 novel ‘The Mayor of Casterbridge’ has formed a terrible rivalry with his erstwhile friend Donald Fafrae and is determined to outdo him in the Casterbridge Cornmarket. He has a hunch about the weather and the price of corn, but needs reassurances. So despite his doubts about the efficacy of prophecy he goes to a lonely hand – built cottage to see ‘a man of curious repute as a forecaster or weather-prophet.’ Henchard is shrouded possibly to protect his identify and he will not stay to take hospitality from the prophet, not cross the threshold, and masks his face with a handkerchief as if suffering from a toothache.

However, the prophet knows this strange man is the former Mayor of Casterbridge, much to Henchard’s surprise. Henchard quizzes him. ‘can ye charm away warts?’ ‘cure the evil?’ ‘forecast the weather?’ Replying in the affirmative he takes Henchard’s crownpiece and forecasts:

“By the sun, moon, and stars, by the clouds, the winds, the trees, and grass, the candle-flame and swallows, the smell of the herbs; likewise by the cats eyes, the ravens, the leeches, the spiders, and the dungmixen, the last fortnight in August will be – rain and tempest.’ ‘Twill be more like living in Revelations this autumn that in England.’

Henchard buys up grain at the current high price, and is ruined by the fine weather that sets in for a fine harvest with corn prices tumbling.

Local folklore was at the heart of many of Hardy’s stories. Perhaps the most dramatic is the ‘Withered Arm’. Gertrude has a withered arm wished upon her by the former lover of her husband, with whom she has an illegitimate boy.

Years pass, and she is still determined to cure her arm. She visits a Casterbridge Cunning Man. He tells her the only cure is to touch the neck of a recently hanged man. So she goes to Casterbridge on a Hanging Day, makes the arrangements with the hangman; touches the neck; is cured immediately, only to find the young man is the illegitimate son of her husband.

I first read these stories one after another at a time I was going through a painful period in my life. I remember throwing the ‘Withered Arm’ at the wall shouting ‘Oh Thomas Hardy’ you miserable man.’ It took me twenty years to come back to him, to appreciate his amazing descriptions of life in rural Wessex, with a cast of characters struggling to make a place for themselves in a world that was changing beyond all recognition.

First Published in 2022, revised July 2024