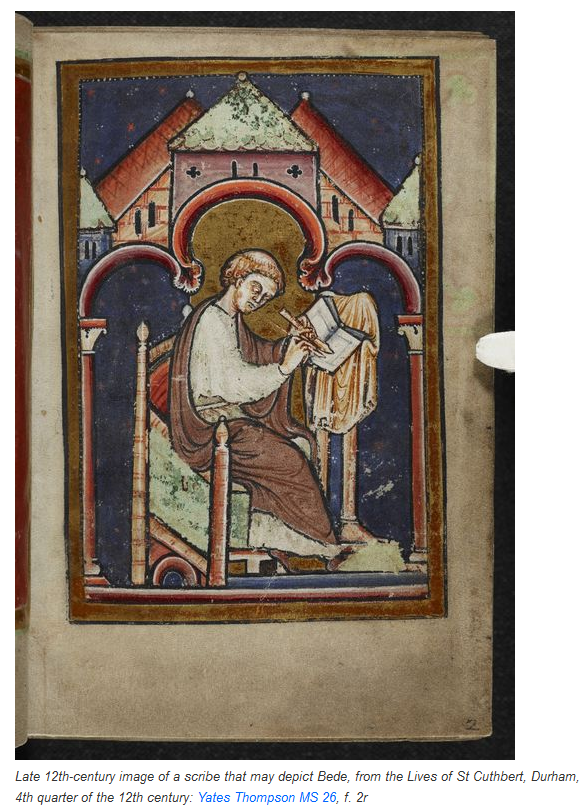

Easter is a Germanic name, and, the only evidence for its derivation comes from the Venerable Bede. He was the first English Historian and a notable scholar. He says the pagan name for April was derived from the Goddess Eostra. The German name for Easter is Ostern probably with a similar derivation. But this is all the evidence there is for the Goddess, despite many claims for the deep history of Easter traditions.

Easter, Estry and Canterbury

Philip A. Shaw has proposed that the name of Eastry in Kent might derive from a local goddess, called Eostra. The influence of Canterbury in the early Church in England and Germany led to the adoption of this local cult name in these two countries. Otherwise, the name for Easter in Europe derives from Pascha which comes from the Hebrew Passover and Latin. In French it’s Pâques, in Italian Pasqua, Spanish Pascua; Dutch Pasen, Swedish Påsk; Norwegian Påske and so on.

The Church’s Choice for the Date of Easter

The timing of Easter is the first full moon after the Spring Equinox. I have already explained that Spring was the time the Church set for the Creation, the Crucifixion and other key points in the Christian Calendar. See my post the-beginning-of-the-universe-as-we-know-it-birthday-of-adam-lilith-eve-conception-of-jesus-start-of-the-year.

Eleanor Parker in her lovely book ‘Winter in the World’ gives a lyrical insight into how the dates were chosen. They held the belief that God would only choose the perfect time for the Creation and the events of Easter. The Creation began with the birth of the Sun and the Moon. So it was fixed to the Equinox, when the days were of equal length, and the fruits of the earth were stirring into life. But Holy Week also needed to be in harmony with the Moon. Therefore it was tied, like Passover, to the first full moon after the Equinox, which is also when the events take place in the Gospels.

The quotations Parker uses from early English religious writing and poetry shows a profound interest in nature and the universe. It is a very appealing viewpoint. It seems to me that this is something the Church, lost in later times, and replaced with fixation with dogma and ‘worship’ of the Holy Trinity.

At the time, fixing the date of Easter was very controversial as the Celtic Church in Britain had a different calendar to the Roman Catholic Church. Easter fell on a different day. The King of Northumberland, for example, celebrated Easter on a different day to that of his wife. Oswiu was exiled to Ireland where he was influenced by Celtic Christianity. His wife, Eanflæd, from Northumberland, had been baptised by the Roman Catholic missionary, Paulinus.

Easter and the Synod of Whitby

Oswiu, became King of Northumberland and ‘Bretwalda’ (ruler of all Britain), and encouraged a reconciliation. This culminated at the Synod of Whitby (664AD), between the two churches. The Celtic Church finally agreed to follow the Catholic calendar and other controversial customs. The Abbess at Whitby during the Synod was Hilda of Whitby. The Celtic position was defended by Bishop Colmán and the Roman position by St Wilfred. Bishop Colmán resigned his position as Bishop of Lindisfarne, returned to Iona and then set up a monastery back in Ireland. Wilfrid studied at Lindisfarne, Canterbury, France and Roman. After her husband’s death, Queen Eanflaed became Abbess of Whitby,

The antagonism between the two churches went back to the time of St Augustine in the early 7th Century. In a meeting between St Augustine and Celtic churchmen, St Augustine was judged to have been arrogant, unwilling to listen. So agreement was not reached. Some time afterwards the Anglo-Saxons attacked the Celts at the Battle of Chester in which hundreds of monks from the Abbey at Bangor were slaughtered.

Days off at Easter & Rituals

King Alfred’s law code gave labourers the week before and after Easter off work, making it the main holiday of the year. Ælfric of Eynsham gives a powerful commentary on the rituals of the Church over Easter. They were full of drama and participation, including Palm leaf processions on Palm Sunday, feet washing and giving offerings to the poor on Maundy Thursday. Then followed three ‘silent days’ with no preaching but rituals and services aiming to encourage empathy for the ordeal of Jesus. This included the nighttime service of Tenebrae. All lights were extinguished in the Church while the choir sang ‘Lord Have Mercy’. The darkness represented the despair that covered the world after Jesus’ death. Good Friday was the day for the adoration of the Cross in which a Cross would be decorated with treasures and symbolised turning a disaster into a triumph.

It seemed to me that I saw a wondrous tree

Lifted up into the air, wrapped in light,

brightest of beams. All that beacon was

covered with gold; gems stood

beautiful at the surface of the earth,….

The Dream of the Rood quoted in Eleanor Parker’s ‘Winter in the World’

The Harrowing of Hell

The days before Easter Sunday are known as the ‘Harrowing of Hell’. This was a very popular theme in the medieval period (featuring in Piers Plowman for example). Jesus went down to hell to free those, like John the Baptist, who had been trapped because the world had no saviour until the first Easter. The name ‘Harrowing’ comes from ‘Old English word hergian ‘to harry, pillage, plunder’ which underpins the way the event is depicted as a military raid on Hell. The ‘Clerk of Oxford’ Blog provides more information on the Harrowing of Hell on this page,

The Clerk of Oxford Blog is written by Eleanor Parker. She started in 2008, whilst an undergraduate student at Oxford. The blog won the 2015 Longman-History Today award for Digital History‘.

The above is but a very poor précis of Eleanor Parker’s use of Anglo-saxon poetry and literature to bring Easter to life. So if you are interested to know more or would like to have a different viewpoint on the Anglo-Saxons please get a copy of her book.

First Published in 2023 and republished in 2025