December comes from the Latin for ten – meaning the tenth month. Of course, it is the twelfth month because the Romans added a couple of extra months especially to confuse us. For a discussion on this, look at an early blog post which explains the Roman Calendar.

In Anglo-Saxon it is ærra gēola which means the month before Yule. In Gaelic it is An Dùbhlachd – the Dark Days which is part of An Geamhrachd, meaning the winter. The word comes from an early Celtic term for cold, from an ‘ancient linguistic source for ‘stiff and rigid’’, which describes the hard frosty earth. (see here for a description of the Gaelic Year). In Welsh, Rhafgyr, the month of preparation (for the shortest day).

For the Christian Church, it’s the period preparing for the arrival of the Messiah into the World. (see my post on Advent Sunday which this year was yesterday November 30th).

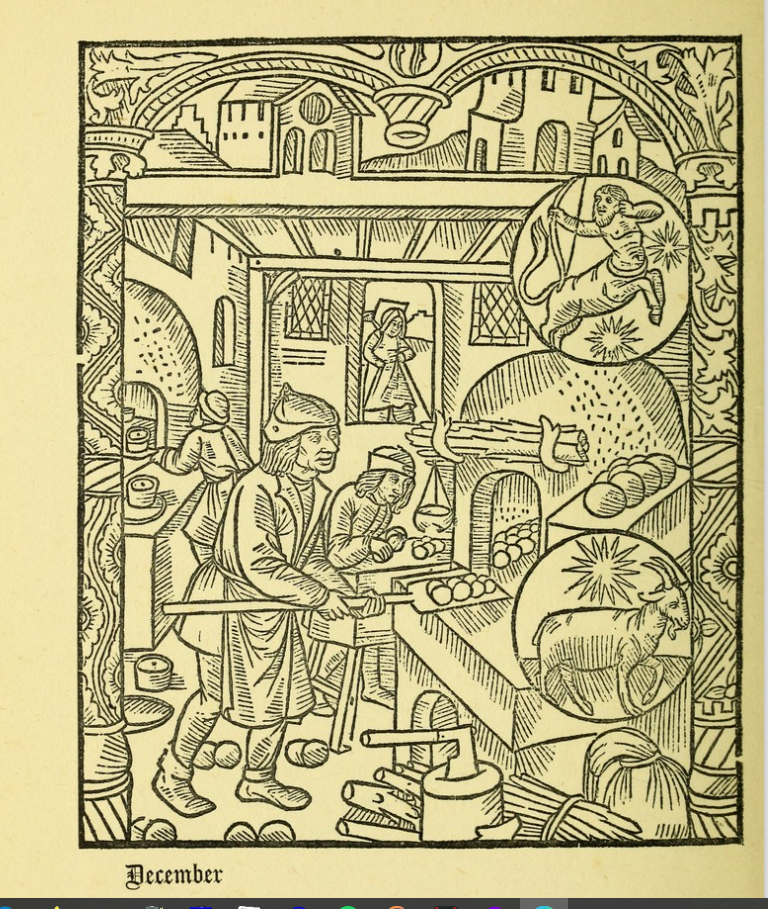

For a closer look at the month, I’m turning to the 15th Century Kalendar of Shepherds. Its illustration (see above) for December shows an indoor scene, and is full of warmth as the bakers bake pies and cakes for Christmas. Firewood has been collected, and the Goodwife is bringing something in from the Garden. The stars signs are Sagittarius and Capricorn.

The Sparrow and the Warm Hall

The Venerable Bede has an interesting story (reported in ‘Winters in the World’ by Eleanor Parker) in which a Pagan, contemplating converting to Christianity, talks about a sparrow flying into a warm, convivial Great Hall, from the bitter cold winter landscape. The sparrow enjoys this warmth, but flies straight out, back into the cold Darkness. Human life, says the Pagan, is like this: a brief period in the light, warm hall, preceded and followed by cold, unknown darkness. If Christianity, he advises, can offer some certainty as to what happens in this darkness, then it’s worth considering.

This contrast between the warm inside and the cold exterior is mirrored in Neve’s Almanack of 1633 who sums up December thus:

This month, keep thy body and head from cold: let thy kitchen be thine Apothecary; warm clothing thy nurse; merry company thy keepers, and good hospitality, thine Exercise.

Quoted in ‘the Perpetual Almanack of Folklore’ by Charles Kightly

December in the ‘Kalendar of Shepherds’

The Kalendar of Shepherds text below gives a vivid description of December weather. Dating from 1626 it gives a detailed look at the excesses of Christmas, which people are on holiday, and who is still working hard. But it concludes it is a costly month.

Six Dozen Years – a Lifespan

The other section of the Kalendar then elaborates on the last six years of a man’s life, with hair going white, body ‘crooked and feeble’. (from 66 to 72). The conceit here is that there are twelve months of the year, and a man’s lot of ‘Six score years and ten’ is allocated six years to each month. So December is not just about the 12th Month of the Year but also the last six years of a person’s allotted span. The piece allows the option of living beyond 72, ‘and if he lives any more, it is by his good guiding and dieting in his youth.’ Good advice, as we now know. But living to 100 is open to but few.

Interesting from my point of view as I have reached the end of my life span as suggested by the Calendar, and my father is 98 and approaching his hundred!

About the Kalendar of Shepherds.

The Kalendar was printed in 1493 in Paris and provided ‘Devices for the 12 Months.’ The version I’m using is a modern (1908) reconstruction of it. It uses wood cuts from the original 15th Century version and adds various texts from 16th and 17th Century sources. (Couplets by Tusser ‘Five Hundred Parts of Good Husbandrie 1599. Text descriptions of the month from Nicholas Breton’s ‘Fantasticks of 1626.) This provides an interesting view of what was going on in the countryside every month.

For more on the Kalendar look at my post here.

The original Kalendar can be read here: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/f4824s6t

To see the full Kalendar, go here:

On This Day

1990 The UK was rejoined to Europe for the first time for 8000 years, when the Channel Tunnellers breached the final wall of rock. French and British workers exchanged flags and shook hands. The Tunnel was opened to traffic in 1994 more than 10 years after work started and 200 years since Napoleon proposed the idea. Read what ICE has to say about the (ICE – Institute of Civil Engineers!).

Britain was connected to the Continent until about 6,100BC, the North Sea, the Channel, and the Irish Sea were all dry (or marshy lands). Water levels were rising and ice melting. the Storegga Slides in Norway saw huge cliffs of ice slipped into the sea. This caused a tsunami over 30ft high and penetrating 25 miles inland. Read the BBC here.

Since then, Britain has been an Island. Archaeologists have been exploring the flooded area which is known as Dogger Land, after the Dogger Bank. (for more on Dogger Land.)

First Published in 2024, republished 2025

Discover more from And Did Those Feet

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I was amazed to learn that the Channel appeared so recently.

Most interesting!