In 2023, I saw my first Daffodil in Hackney in a Council Estate on 12 January. My first daffodil in 2024 was outside my first floor window in early February. In 2025, I can see the shoots of Daffodils in my garden but nothing blooming. However, there are the first daffodils in my area by the side of a different Council Estate. They bring such joy and hope for the return of the Sun.

Narcissus the Flower

Their formal name is Narcissus. The Roman natural historian, Pliny tells us that the plant was:

‘named Narcissus from narkē not from the fabulous boy.’

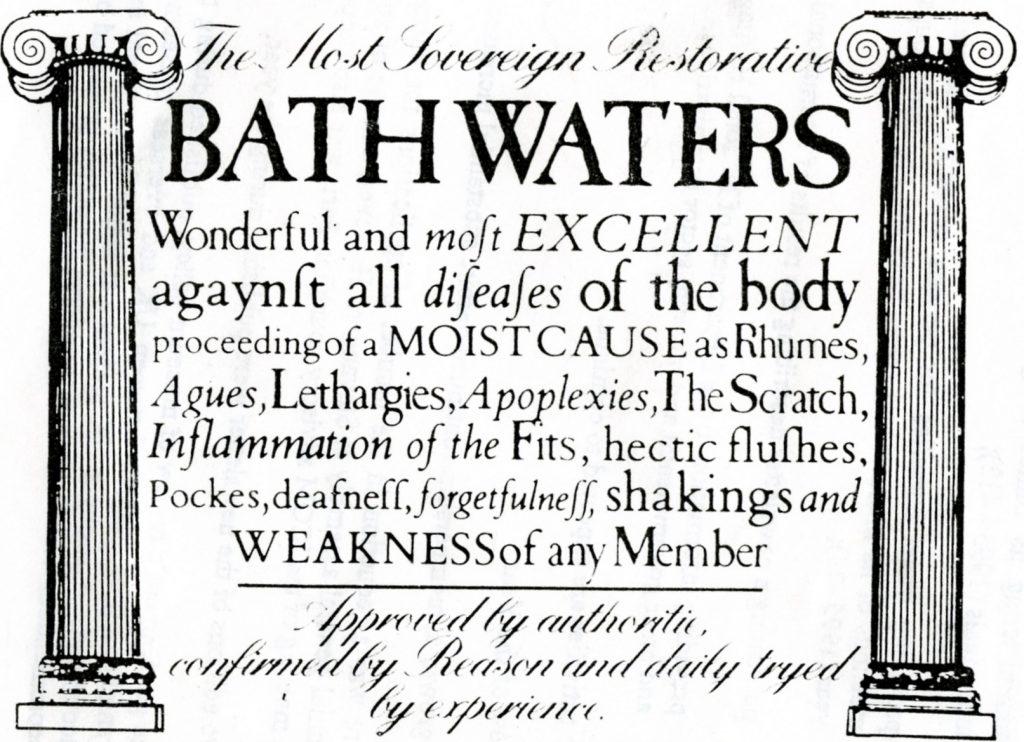

Narkē is the Greek word from which we derive the word narcotic. It is a reference to the narcotic properties of the narcissus. An extract of the bulb applied to open wounds produced numbness of the whole nervous system and paralysis of the heart. The flowers are also slightly poisonous. So, they were used as an emetic. They brought on vomiting when it was felt necessary that the stomach be emptied. It was used to treat hysteria and epilepsy. They treated children with bronchial catarrh or epidemic dysentery. Among Arabian doctors, it was used to cure baldness and as an aphrodisiac. (Source: A Modern Herbal by Mrs M Grieve.) Please remember these are not recommendations for use medicinally, but are historic uses and may be dangerous.

Daffodils & Narcissus the Fabulous Boy

The fabulous boy, mentioned by Pliny, was Narcissus. He, according to the Roman Poet Ovid, met the nymph Echo, and she fell in love with the beautiful boy. He spurned her, and she faded until all that remained of her was her voice – the echo we hear.

Nemesis, the Goddess of Revenge (the one with the fiery sword) decided on revenge upon the handsome boy. She lured the thirsty youth to a fountain, where he saw an image of a breathtakingly handsome boy. He fell instantly in love with such beauty. But it was an image of himself. Realising he would never meet anyone as fabulous as himself, he faded from life. He eventually metamorphised into a white and yellow flower, which was named after him.

Daffodils & Shakespeare

Daffodils are mentioned in a list of Spring Flowers by Shakespeare in the pastoral play The Winter’s Tale:

(Please note that as you read Shakespeare’s words below that Prosperpina is the wife of Pluto, the God of the Underworld, Dis, is another name for him, Cytherea is the Goddess of Beauty and Love. Phoebus is the Sun God. And the Spring Flowers are Daffodils, violets, primroses, oxlips(primula), Crown Imperial (Fritillaria imperialis), Lilies, flower-De-luce (Iris)

Perdita to Camillo

Out, alas!

You’d be so lean that blasts of January

Would blow you through and through.

(To Florizel)

I would I had some flowers o’th’ spring, that might

Become your time of day –

(to the Shepherdesses)

That wear upon your virgin branches yet

Your maidenheads growing. O Proserpina,

For the flowers now that, frighted, thou let’st fall

From Dis’s waggon! Daffodils,

That come before the swallow dares, and take

The winds of March with beauty; violets, dim,

But sweeter than the lids of Juno’s eyes

Or Cytherea’s breath; pale primroses,

That die unmarried ere they can behold

Bright Phoebus in his strength – a malady

Most incident to maids; bold oxlips and

The crown imperial; lilies of all kinds,

The flower-de-luce being one: O, these I lack

To make you garlands of, and my sweet friend

To strew him o’er and o’er!WT IV.iv.110.2

The reference to Daffodils suggests that for Shakespeare they are around to withstand the March Winds before the Swallows arrive in April. With selective breeding, early flowering species have been developed. Now February and even January are within the scope of the glorious bulb. (here is a post on winter flowering varieties)

Below is the text of Ovid’s Echo and NarcissusTranslated by Brookes Moore

NARCISSUS AND ECHO, THE HOUSE OF CADMUS

Once a noisy Nymph, (who never held her tongue when others spoke, who never spoke till others had begun) mocking Echo, spied him as he drove, in his delusive nets, some timid stags.—For Echo was a Nymph, in olden time,—and, more than vapid sound,—possessed a form: and she was then deprived the use of speech, except to babble and repeat the words, once spoken, over and over. Juno confused her silly tongue, because she often held that glorious goddess with her endless tales, till many a hapless Nymph, from Jove’s embrace, had made escape adown a mountain. But for this, the goddess might have caught them. Thus the glorious Juno, when she knew her guile; “Your tongue, so freely wagged at my expense, shall be of little use; your endless voice, much shorter than your tongue.” At once the Nymph was stricken as the goddess had decreed;—and, ever since, she only mocks the sounds of others’ voices, or, perchance, returns their final words.

One day, when she observed Narcissus wandering in the pathless woods, she loved him and she followed him, with soft and stealthy tread.—The more she followed him the hotter did she burn, as when the flame flares upward from the sulphur on the torch. Oh, how she longed to make her passion known! To plead in soft entreaty! to implore his love! But now, till others have begun, a mute of Nature she must be. She cannot choose but wait the moment when his voice may give to her an answer. Presently the youth, by chance divided from his trusted friends, cries loudly, “Who is here?” and Echo, “Here!” Replies. Amazed, he casts his eyes around, and calls with louder voice, “Come here!” “Come here!” She calls the youth who calls.—He turns to see who calls him and, beholding naught exclaims, “Avoid me not!” “Avoid me not!” returns. He tries again, again, and is deceived by this alternate voice, and calls aloud; “Oh let us come together!” Echo cries, “Oh let us come together!” Never sound seemed sweeter to the Nymph, and from the woods she hastens in accordance with her words, and strives to wind her arms around his neck. He flies from her and as he leaves her says, “Take off your hands! you shall not fold your arms around me. Better death than such a one should ever caress me!” Naught she answers save, “Caress me!” Thus rejected she lies hid in the deep woods, hiding her blushing face with the green leaves; and ever after lives concealed in lonely caverns in the hills. But her great love increases with neglect; her miserable body wastes away, wakeful with sorrows; leanness shrivels up her skin, and all her lovely features melt, as if dissolved upon the wafting winds—nothing remains except her bones and voice—her voice continues, in the wilderness; her bones have turned to stone. She lies concealed in the wild woods, nor is she ever seen on lonely mountain range; for, though we hear her calling in the hills, ’tis but a voice, a voice that lives, that lives among the hills.

Thus he deceived the Nymph and many more, sprung from the mountains or the sparkling waves; and thus he slighted many an amorous youth.—and therefore, some one whom he once despised, lifting his hands to Heaven, implored the Gods, “If he should love deny him what he loves!” and as the prayer was uttered it was heard by Nemesis, who granted her assent.

There was a fountain silver-clear and bright, which neither shepherds nor the wild she-goats, that range the hills, nor any cattle’s mouth had touched—its waters were unsullied—birds disturbed it not; nor animals, nor boughs that fall so often from the trees. Around sweet grasses nourished by the stream grew; trees that shaded from the sun let balmy airs temper its waters. Here Narcissus, tired of hunting and the heated noon, lay down, attracted by the peaceful solitudes and by the glassy spring. There as he stooped to quench his thirst another thirst increased. While he is drinking he beholds himself reflected in the mirrored pool—and loves; loves an imagined body which contains no substance, for he deems the mirrored shade a thing of life to love. He cannot move, for so he marvels at himself, and lies with countenance unchanged, as if indeed a statue carved of Parian marble. Long, supine upon the bank, his gaze is fixed on his own eyes, twin stars; his fingers shaped as Bacchus might desire, his flowing hair as glorious as Apollo’s, and his cheeks youthful and smooth; his ivory neck, his mouth dreaming in sweetness, his complexion fair and blushing as the rose in snow-drift white. All that is lovely in himself he loves, and in his witless way he wants himself:—he who approves is equally approved; he seeks, is sought, he burns and he is burnt. And how he kisses the deceitful fount; and how he thrusts his arms to catch the neck that’s pictured in the middle of the stream! Yet never may he wreathe his arms around that image of himself. He knows not what he there beholds, but what he sees inflames his longing, and the error that deceives allures his eyes. But why, O foolish boy, so vainly catching at this flitting form? The cheat that you are seeking has no place. Avert your gaze and you will lose your love, for this that holds your eyes is nothing save the image of yourself reflected back to you. It comes and waits with you; it has no life; it will depart if you will only go.

Nor food nor rest can draw him thence—outstretched upon the overshadowed green, his eyes fixed on the mirrored image never may know their longings satisfied, and by their sight he is himself undone. Raising himself a moment, he extends his arms around, and, beckoning to the murmuring forest; “Oh, ye aisled wood was ever man in love more fatally than I? Your silent paths have sheltered many a one whose love was told, and ye have heard their voices. Ages vast have rolled away since your forgotten birth, but who is he through all those weary years that ever pined away as I? Alas, this fatal image wins my love, as I behold it. But I cannot press my arms around the form I see, the form that gives me joy. What strange mistake has intervened betwixt us and our love? It grieves me more that neither lands nor seas nor mountains, no, nor walls with closed gates deny our loves, but only a little water keeps us far asunder. Surely he desires my love and my embraces, for as oft I strive to kiss him, bending to the limpid stream my lips, so often does he hold his face fondly to me, and vainly struggles up. It seems that I could touch him. ‘Tis a strange delusion that is keeping us apart. Whoever thou art, Come up! Deceive me not! Oh, whither when I fain pursue art thou? Ah, surely I am young and fair, the Nymphs have loved me; and when I behold thy smiles I cannot tell thee what sweet hopes arise. When I extend my loving arms to thee thine also are extended me—thy smiles return my own. When I was weeping, I have seen thy tears, and every sign I make thou cost return; and often thy sweet lips have seemed to move, that, peradventure words, which I have never heard, thou hast returned. No more my shade deceives me, I perceive ‘Tis I in thee—I love myself—the flame arises in my breast and burns my heart—what shall I do? Shall I at once implore? Or should I linger till my love is sought? What is it I implore? The thing that I desire is mine—abundance makes me poor. Oh, I am tortured by a strange desire unknown to me before, for I would fain put off this mortal form; which only means I wish the object of my love away. Grief saps my strength, the sands of life are run, and in my early youth am I cut off; but death is not my bane—it ends my woe.—I would not death for this that is my love, as two united in a single soul would die as one.”

He spoke; and crazed with love, returned to view the same face in the pool; and as he grieved his tears disturbed the stream, and ripples on the surface, glassy clear, defaced his mirrored form. And thus the youth, when he beheld that lovely shadow go; “Ah whither cost thou fly? Oh, I entreat thee leave me not. Alas, thou cruel boy thus to forsake thy lover. Stay with me that I may see thy lovely form, for though I may not touch thee I shall feed my eyes and soothe my wretched pains.” And while he spoke he rent his garment from the upper edge, and beating on his naked breast, all white as marble, every stroke produced a tint as lovely as the apple streaked with red, or as the glowing grape when purple bloom touches the ripening clusters. When as glass again the rippling waters smoothed, and when such beauty in the stream the youth observed, no more could he endure. As in the flame the yellow wax, or as the hoar-frost melts in early morning ‘neath the genial sun; so did he pine away, by love consumed, and slowly wasted by a hidden flame. No vermeil bloom now mingled in the white of his complexion fair; no strength has he, no vigor, nor the comeliness that wrought for love so long: alas, that handsome form by Echo fondly loved may please no more.

But when she saw him in his hapless plight, though angry at his scorn, she only grieved. As often as the love-lore boy complained, “Alas!” “Alas!” her echoing voice returned; and as he struck his hands against his arms, she ever answered with her echoing sounds. And as he gazed upon the mirrored pool he said at last, “Ah, youth beloved in vain!” “In vain, in vain!” the spot returned his words; and when he breathed a sad “farewell!” “Farewell!” sighed Echo too. He laid his wearied head, and rested on the verdant grass; and those bright eyes, which had so loved to gaze, entranced, on their own master’s beauty, sad Night closed. And now although among the nether shades his sad sprite roams, he ever loves to gaze on his reflection in the Stygian wave. His Naiad sisters mourned, and having clipped their shining tresses laid them on his corpse: and all the Dryads mourned: and Echo made lament anew. And these would have upraised his funeral pyre, and waved the flaming torch, and made his bier; but as they turned their eyes where he had been, alas he was not there! And in his body’s place a sweet flower grew, golden and white, the white around the gold.

First published in February 2023, revise and republished in February 2024, 2025