So, yesterday, you, being someone worried about your eyes, might have sought out an altar dedicated to St Lucy, the patron saint of eye health. (see December 13th’s Post on St Lucy) Although you may be disappointed that there has been no miraculous cure, you might have been encouraged to do something about it. So that’s what this post is about.

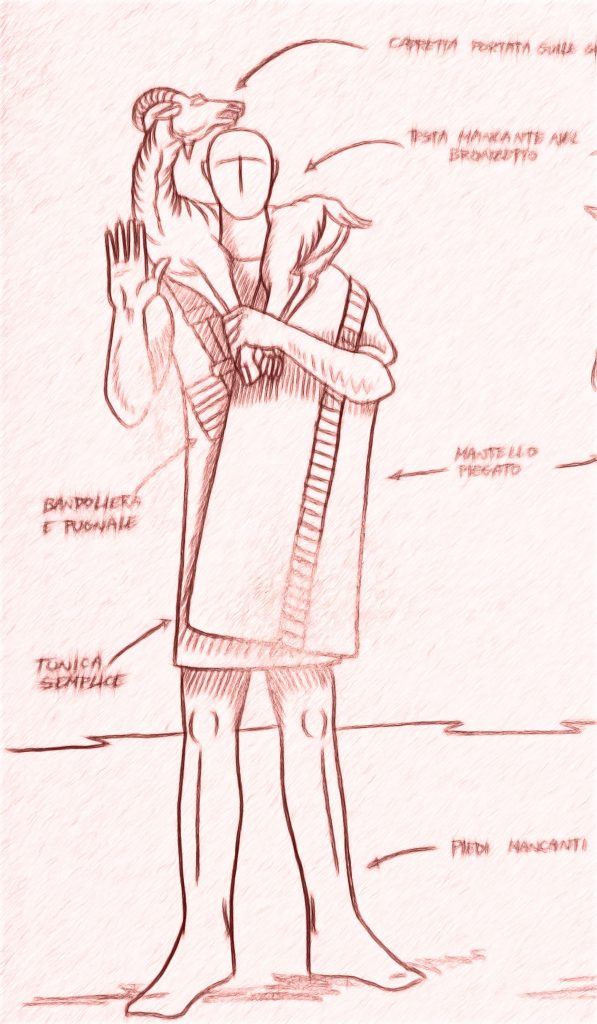

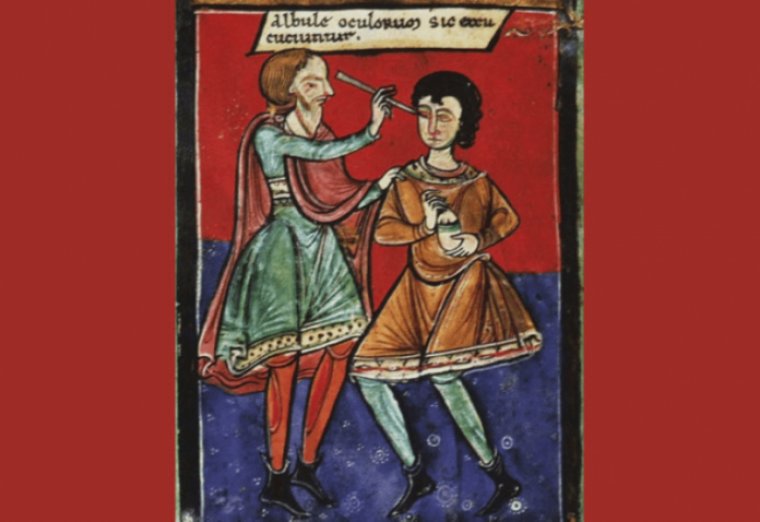

Cataract operations have been carried out since 800 BC using a method called ‘couching’.

“The practitioner would sit facing the patient and pass a long needle through the cornea to impale the lens. “He would then forcibly dislodge the lens — rupturing the zonules — and push it into the vitreous cavity, where it would hopefully float to the bottom of the eye and out of the visual axis.”

Evolution of Cataract Surgery.

This was a last resort when the cataract was opaque and the patients nearly blind. It would mean they would need very thick lenses to see well again but, crude as it seems, it worked. But the operation, without anaesthetics must have been a considerable ordeal, and the recovery (still required today for those suffering from a displaced retina) means that the patient has to lie on their back for a week with supports on either side of the head to prevent movement. Of course, there was also a serious risk of infection, so prophylactic visits to a chapel of St Lucy would be called for.

The modern system was established in the 1940s and offers a great solution in 15 minutes surgery. Currently, the NHS has been having trouble dealing with all the cases required, (6% of surgery is for cataract operations. Before COVID-19, there was some talk about cataracts being, in practice, not readily available on the NHS. The waiting time is supposed to be 18 weeks but, for example, at NHS Chesterfield Royal Hospital the waiting time approaches almost 10 months. But waiting times vary from 10 weeks to over a year.

Pink Eye

The Perpetual Calendar of Folklore by Charles Kightly has dug up some other folk cures of interest.

For the redness of eyes, or bloodshot. Take red wine, rosewater, and women’s milk, and mingle all these together: and put a piece of wheaten bread leavened, as much as will cover the eye, and lay it in the mixture. When you go to bed, lay the bread upon your eyes calmer and it will help them.

Fairfax Household book, 17th/ 18th century.

There are many household books still, existing, which show that much of medical practice was carried out in the home, and that men and women, more often women, actively not only collected useful recipes and cures, but also tested them out and improved them.

As a matter of curiosity, there is a significant document found at the Roman Fort of Vindolanda which lists the troops of the Cohort in occupation, which notes that of the garrison of 750, 474 are absent with 276 in the fort of which 38 are sick, 10 with ‘pink eye’, probably conjunctivitis

Prevention is better than cure

Things hurtful to the eyes. Garlic, onions, radish, drunkenness, lechery, sweet wines, salt meats, coleworts, dust, smoke, and reading presently after supper.

Good for the eyes. fennel, celandine, eyebright, vervain, roses, cloves and cold water.

Whites Almanack 1627

Looking through Samuel Pepys’s eye

You will note, above, that it was considered bad for the eyes to read in low light. It is a myth and not true. Samuel Pepys was continually worried about his reading and writing habits ruining his eyesight. This is an extract from the poignant last entry in his famous diary:

And thus ends all that I doubt I should ever be able to do with my own eyes in the keeping of my journal, I being not able to do it any longer, having done now so long as to undo my eyes almost every time that I take a pen in my hand; and therefore, whatever comes of it, I must forbear: and therefore resolve from this time forward to have it kept by my people in long-hand. I must be consented to sit down no more than is fit for them and all the world to know; or, if they be anything, which cannot be much now my amores are past and my eyes hindering me almost all other pleasures. I must endeavour to keep a margin in my book open, to add, here and there, a note in shorthand with my own hand.

Samuel Pepys Diary, May 31st

The sad thing is that Pepys had another 38 years before he went blind, and what glorious diary entries have we missed because of his false fears of the effect of eye strain.

St Lucy

There are only two churches in the UK dedicated to St Lucy or St Lucia. One run by the National Trust in Upton Magna, Shropshire, but there must have been a few chapels in Cathedrals and Abbeys dedicated to her.

First published in 2022, updates 2023, and 2024