The Moon rules the months: this month’s span ends

With the worship of the Moon on the Aventine Hill.

Fasti by Ovid

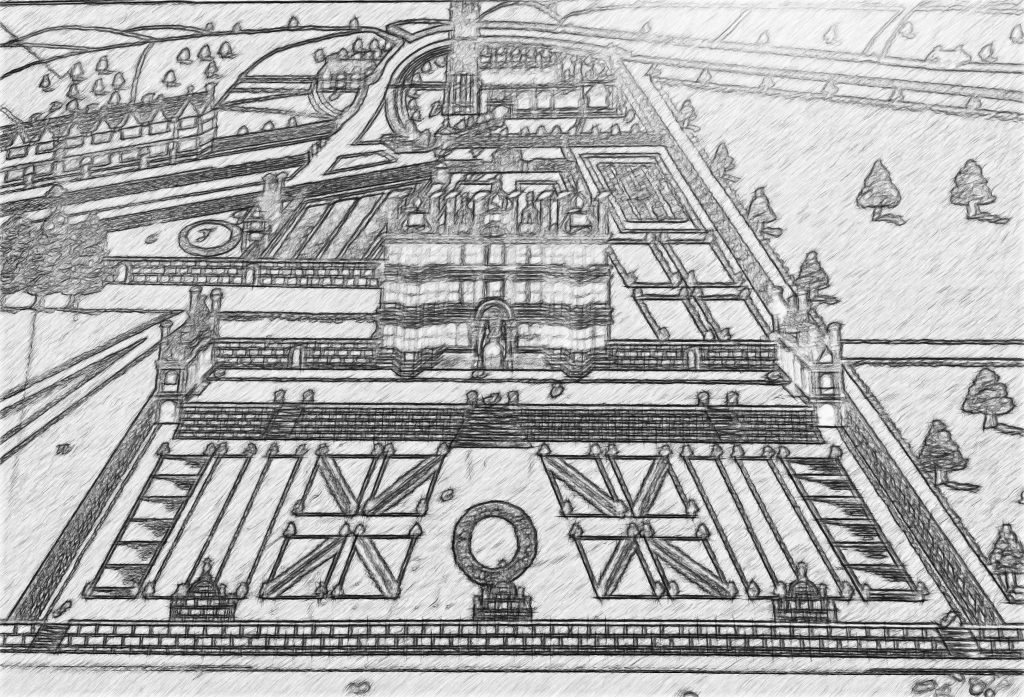

The Aventine Hill is one of the seven hills of Rome, named after a mythical King Aventinus. It is the hill upon which Hercules pastured his cattle, which were stolen by Cacus. According to Virgil in his Aeneid, the monstrous Cacus lived in a cave on a rocky slope near the River Tiber. Cacus was the son of Vulcan, the artificer God. He was, also, a fire breathing Giant who eat human flesh and stuck their skulls on the door of his house. When Hercules wrestled with him, he hugged him so tight Cacus’ eyes popped out of his head.

The worship of Minerva also took place on the Hill. You can take a Google Earth fly past if you follow this link – also some nice photos, and a link to Wikipedia.

The Aventine Hill & Romulus

The Hill is famous in the mythology of Rome because it is associated with Romulus. He and his twin Brother Remus, were born to the vestal virgin, Rhea Silvia, in the pre-Roman City of Alba Longa, not far away. Rhea was the daughter of former King Numitor. Her uncle, killed Rhea’s brother and forced her to be a vestal Virgin. This ensuring Numitor’s line died out.

But, in her sacred grove she was put to sleep by Somnus dripping a sleeping draft into her eyes and then raped by the God Mars. This was a terrible breaking of the taboo for Vestal Virgins. Rhea gave birth to the twin boys. They had to be hidden from the wrath of their Granduncle.

The Palatine & the Lupercal

The boys were saved by the River God Tiberinus and then by being suckled by a Wolf in a cave called the Lupercal, which is at the foot of the Palatine Hill in Rome. A ‘grotto’ under Augustus’ Palace on the Palatine, has been claimed as the original Lupercal, but it is disputed. (see www.digitalaugustanrome.org/records/lupercal/.

When they grew up, they helped their Grandfather (Numitor) reclaim the throne of Alba Longa. The boys, being the children of the War God, were obviously excellent at the art of war. Then they decided to found their own City, but they could not decide upon which hill to build it or whom to name it after (accounts vary!). Remus favoured the Aventine, Romulus the Palatine (some accounts say vice versa).

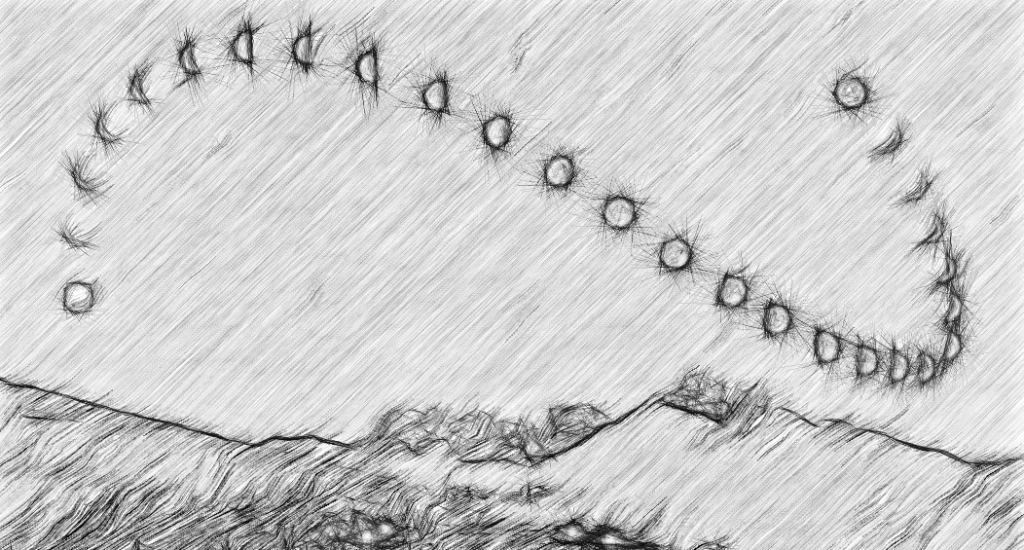

So they decided to let the Gods decide. Remus claimed to have won when he saw a flight of 6 auspicious birds. Romulus saw 12 and declared himself the winner. And the City was named Rome in his honour. It was on his choice of Hill – the Palatine Hill. The Aventine hill was, originally, outside the City boundary.

The two fell out and Remus was killed. This story was first written down in the Third Century BC, and it was claimed that Rome was founded in 753BC. These stories continue to be told and celebrated. In Britain, we largely ignore our creation myths. Despite our legendary Founder, King Brutus, being a relative of Romulus and Remus.

For more on Mars and Vesta see my post:

More on King Brutus see my post;

Selene, the Moon Goddess see my post:

First written in 2023 and revised March 30th 2024, 2025

![Chad is the patron saint of medicinal springs,[37] although other listings[38] do not mention this patronage.

St. Chad's Day (2 March) is traditionally considered the most propitious day to sow broad beans in England.](https://www.chr.org.uk/anddidthosefeet/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/haggerston_may_2020.jpg)