Vortigern was chosen as leader of Britannia immediately after the Romans withdrew in the early 5th Century AD. His name means Great Leader in Brittonic. He is one of the few leaders we know to be a real person in what used to be called the Dark Ages. We accept him as real, as he appears in the near contemporary source by the Monk Gildas.

However, very little is known of him except legends. He was associated with Merlin. Legend accuses him of betraying the British for the lust for Rowena. She was the daughter of the Saxon Leader Hengist. Whatever the truth of this, he continued the late Roman policy of hiring Germanic mercenaries. They were used to defend against the many barbarian threats to the Empire. The threats to Britain including the Picts, the Irish, and, of course the Saxons. The legends say that Hengist and Horsa were hired with their three ‘keels’ of Saxon mercenaries. In payment for services rendered, or for lust, Vortigern surrendered the sovereignty of Kent to the Saxons. Thus began the so-called ‘Adventus Saxonum’, and the destruction of the power of the Britons.

Kent and the Survival of pre-Saxon names

How much of this is ‘true’ we have no idea. But the name of Kent survives from the prehistoric, into the Roman. And unlike most tribal names survives to the modern day. This is probably because it was the first Roman Civitas to be taken over by the Saxons. Most likely still largely a working political unit. So it kept its name. The other Roman political units mostly lost their names in the anarchy of this period. Who now has heard of the Trinovantes, the Catuvellauni, or the Atrebates? The political boundaries from the Prehistoric period survived through the Roman period. But mostly did not survive the fall of Rome.

For more legends of this period look at my post

Vortigern & Rowena the Play

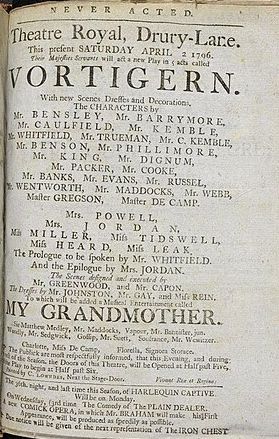

In 1796, a great cast at the Drury Lane Theatre, owned and managed by Sheridan, put on a newly discovered play by William Shakespeare. The cast included Kemble, Barrymore, and Mrs Jordan who was the mistress of Prince William (aka William III). Rumours swirled around about the authenticity of the play. Shakespeare was interested in Britain’s legendary history having written Cymberline and King Lear. But critics thought it was too simple to be genuine. Eventually, William Henry Ireland admitted he was the author.

‘A London Year’ by Travis Elborough and Nick Rennison has a great quote from a visit to the play. It took place on April 2nd 1796 and is recorded in Joseph Farington’s diary. Compare this description to your last polite experience at the Theatre.

Shakespeare’s forgery staged

Island’s play of Vortigern, I went to. Prologue, spoken in 35 minutes past six, play over at 10. A strong party was evidently made to support it, which clapped without opposition frequently through near three acts. When some ridiculous passages caused a laugh, which infected the house during the remainder of the performance, mixed with groans. Kemble requested the audience to hear the play out about the end of the fourth act, and prevailed. The epilogue was spoken by Mrs. Jordan, who skipped over some lines which claimed the play as Shakespeare’s

Barrymore attempted to give the play out for Monday next, but was hooted off the stage. Kemble then came on. And after some time, was permitted to say that ‘School for Scandal’ would be given, which the house approved by clapping.

Sturt of Dorsetshire was a Stage Box drunk and exposed himself indecently to support the play. And when one of the stage attendants attempted to take up the green cloth, Sturt seized him roughly by the head. He was slightly pelted with oranges. Ireland, his wife, a son and a daughter and two others were in the centre box at the head of the Pitt. Ireland occasionally clapped. But towards the end of the fourth act, he came into the front row and for a little time, leaned his head on his arm. And then went out of the box and behind the scenes. The Playhouse contained an audience that amounted to £800 pounds.

April 2nd 1796 from Joseph Farington’s Diary, (I have changed some of the punctuation.)

On This Day

Today is St. Urban of Langres Day.

He is the patron of Langres; Dijon; vine-growers, vine-dressers, gardeners, vintners, and coopers. And invoked against blight, frost, storms, alcoholism, and faintness. (www.catholic.org/saints/) But is also called upon to make maid’s hair long and golden.

On the feast of St Urban, (forsooth) maids hang up some of their hair before the image of St Urban, because they would have the rest of their hair grow long and golden.

Reginald Scott, the Discovery of Witchcraft, 1584. (Thanks to the Perpetual Almanac by Charles Kightly.) For more on Reginald Scott and Witches see my post.

1744 – First Golf Tournament. No, not at St Andrews but at Leith Links, Edinburgh.

First Published, 2nd April 2025