London Bridge to Bermondsey 11am Sun 8th Feb 26 To book

Roman London – Literary & Archaeology Walk 2.15pm Feb 8th 26 To book

The Rebirth Of Saxon London Archaeology Walk 11am Sun 22nd Feb 26 To book

Jane Austen’s London Walk 2.15pm Sun 22nd Feb 26 To book

London Before London – Prehistoric London Virtual Walk 7:30pm Mon 23rd Feb26 To book

London. 1066 and All That Walk 11.30am Sun 8th March 2026 To book

Tudor London – The City of Wolf Hall 2.30 8th March 2026 Barbican Underground Station To book

The Spring Equinox London Virtual Tour 7.30pm Fri 20th March26 To book

The Decline And Fall Of Roman London Walk 11.30 Sat 21st March26 To book

The London Equinox and Solstice Walk 2:30pm Sat 21st March26 To book

Roman London – Literary & Archaeology Walk 11.15pm Sun April 5th 2026 To book

Samuel Pepys’ London – Bloody, Flaming, Poxy London 2:15pm Sun 5th April 26 To book

Chaucer’s Medieval London Guided Walk 11.00am Sat 18th April 2026 To book

Chaucer’s London To Canterbury Virtual Pilgrimage 7.45pm Sat 18th April 26 To book

Jane Austen’s London Walk 11.00am Sun 19th April 26 To book

Myths, Legends, Archaeology, and the Origins of London 11:15am Sat 2nd May 26 to Book

For a complete list of my guided walks for London Walks in 2025 look here

St Blaise Day & The Tadpole Revels February 3rd

The Blessing of St Blaise helps protect the throat. The way it is works is that blessed candles are made into a cross. These are then touched against the throat of the afflicted one. Why? Because a story was told that Blaise, on his way to martyrdom, cured a boy who had a fish bone stuck in his throat. So, he is the patron Saint of Sores Throats.

Blaise is thought to have been an Armenian Bishop of Sebaste, martyred (316AD) in the persecution of the Emperor Licinius.

Sage Advice for Sore Throats:

In the spirit of St Blaise, here is advice for care of your throats.

Sage Tea is said to be excellent for many things, including dental hygiene and alleviating sore throats. The Kalendar of Shepherds tells us how to treat our throats:

Good for the throat honey, sugar, butter with a little salt, liquorice, to sup soft eggs, hyssop, a mean manner of eating and drinking and sugar candy. Evil for the throat: mustard, much lying on the breast, pepper, anger, things roasted, lechery, much working, too much rest, much drink, smoke of incense, old cheese and all sour things are naughty for the throat.

The Kalendar of Shepherds 1604

The Martyrdom of St Blaise

So far, an uplifting, healing story. However, the Medieval Church’s propensity for the gruesome and its peculiar need to allocate a unique method of martyrdom to each early saint leads us to Blaise being pulled apart by wool-combers irons. Then he was beheaded.

Hence, he is also the patron saint of wool-combers, and by extension, sheep. Wikipedia tells me that ‘Combing: was a regular form of torture.

Combing, sometimes known as carding (despite carding being a completely different process) is a sometimes-fatal form of torture in which iron combs designed to prepare wool and other fibres for woollen spinning are used to scrape, tear, and flay the victim’s flesh.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Combing_(torture)

Gory Martyrdoms Explained?

I am horrified by the goriness of these martyrdoms, and it needs some explanation. If we believe in Richard Dawkins idea of the meme we can find an explanation. Allocating a different and gory death to each and every saint has advantages for the survival of the cult. It brings a uniqueness to the story of the Saint. Particular details of death suggests authenticity. The extreme death creates an example of stoicism in the face of challenge to faith, and provokes empathy and piety. There is, also, we have to accept, a very human attraction in the bloodthirstiness of stories.

But, there is, I suspect, a financial interest too. In order for these cults to survive, they need adherents, acolytes, worshippers, donors, patrons. They require income streams that can help support the expensive clergy and the fabric of the Church or chapel. One source of income is from the wealthy, but in the medieval town, urban wealth was held within the booming guild structure. If the martyred Saint, could attract a particular Guild then (the sponsoring Priests, or Church) were quids in.

Wool was the mainstay of the economy in the medieval period. A martyr like St Blaise would prosper wherever there were people working with wool, cloth or sheep. So, is it too cynical to suggest someone with an eye for the main chance added the detail of the wool combing death to attract donations from rich wool merchants? As a successful meme, it spread throughout Europe.

Also, there were any number of endemic diseases and occupational hazards for which there was no clear cure. So if the Saint can become the Saint of common, preferably chronic, illnesses, he/she can attract all those who suffer from that or similar diseases.

Of course, it may not always be a cynical drive for more income. In exchange, the Church offered the sufferer comfort in the face of suffering. This quality is not only of great use on its own, but it would have maximised the placebo effect. The effect has been scientifically measured. And would often be more effective a cure as than the available, often bizarre, medieval remedies.

Blaise’s hagiography suggests he was a physician. The cult was able to grow into being not only the Saint for Sore Throats and Sheep but one of the go-to saints for diseases in both humans and animals.

For a female tortured Saint see my post of St Margaret of Antioch here.

Blaise in Britain

His cult came to Britain when King Richard I was ship wrecked on Crusade. Richard was helped by Bishop Bernard of Ragusa where Richard was washed up. When the Bishop was deposed he sought sanctuary in Britain and was made Bishop of Carlisle where he promoted the cult of Blaise. Several churches in the UK founded churches named for him.

St Blazey in Cornwall is named after his Church and celebrates him by a procession of a ram and a wicker effigy of the Saint. Milton, in Berkshire, dedicated its Church to St Blaise, probably because the village’s wealth depended on sheep. The village held a feast on the third Sunday after Trinity, and the day after held the Tadpole Revels at Milton Hall. Tadpole is thought to be a corruption from the word ‘Tod’ which means cleaned wool.

Blaise in London

Westminster Abbey has a chapel dedicated to Blaise (see image at top of page). In the Bishop’s Palace at Bromley is St Blaise’s Well. It is thought to have begun as a spring when the Palace ‘was granted to Bishop Eardwulf by King Ethelbert II of Kent around 750 AD.’ A well near the spring became a place of pilgrimage and an Oratory to St Blaise was set up. In the 18th Century, the chalybeate waters of the well were considered to be useful for health. It still exists today.

On February 3rd, St Etheldreda’s Church in London holds the Blessing of the Throats ceremony. It was a Catholic Church in the medieval period, then, in Reformation was used for various purposes until returned to the Catholic Church in 1876. It has memorials for Catholic Martyrs killed in the reign of Queen Elizabeth I

CC BY-SA 4.0 Wikipedia St Etheldreda’s Church

One of London’s oldest guilds is the Worshipful Company of Woolmen, first mentioned in 1180, when fined, for operating without a license, by Richard 1’s dad, Henry II.

Sources: The Perpetual Almanac by Charles Kightly, Woolly Saints, Britannica, Wovember, wikipedia.

On This Day

1637 – Tulip Mania dramatic collapse of the soaring price of Tulip Bulbs within the Dutch Republic.

1761 – At the age of 87 Beau Nash, Master of Ceremonies at Bath died. To see my post on 18th Century Bath please look at March 14th

1870 – The 15th Amendment to the US Constitution was ratified. It prohibits the federal government or any state from denying or abridging a citizen’s right to vote “on account of race, colour, or previous condition of servitude”. What I don’t understand is how this is compatible with all the many ‘abridgements’ of a citizen’s right to vote which seem to flourish. In particular, Gerrymandering. Isn’t it effectively an abridgement of the right to vote, if the electoral districts are so artificially engineered as to make that vote meaningless? Maybe it’s ok if the abridgement is not about race, colour etc.? (OK as in ‘get away with subverting democracy’.

1917 – World War I: The USA enters the War (unrestricted submarine warfare being one of the causes)

1933 – The policy of Lebensraum announced by Adolf Hitler. This might be explained as one powerful country saying it is entitled to take over less powerful countries because they can?

Revised 2025, and 2026

Candlemas February 2nd

Candlemas is an important festival of the Church, celebrated throughout the Christian world. It is the day Jesus was presented to the Temple as a young boy and prophesied to be ‘a light to lighten the Gentiles’. The day is therefore celebrated by lighting candles. Hence its name.

It is also called the Feast of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary. It is 40 days after the birth of Jesus which was fixed as the 25th December by Pope Liberius by AD 354. So it is the end of the postpartum period ‘as the mother’s body, including hormone levels and uterus size, returns to a non-pregnant state’. Mary went to the Temple to be ritually cleansed. This later became known as ‘churching’.

Candlemas a Cross Quarter Day.

It is also one of the cross quarter days of the Celtic tradition, that is halfway between Winter Solstice and May Day. The candles also suggest a light festival marking the lengthening days. It is probably another of those festivals where the Christian Church has taken on aspects of the pagan rituals, so Brigantia’s (celebrated at Imbolc on February 1st) role in fertility is aligned with the Virgin Mary’s.

Weather Lore for Candlemas

Folklore prophecies for today: ‘If it is cold and icy, the worst of the winter is over, if it is clear and fine, the worst of the winter is to come.’ Looking overhead I can see a little blue sky but I can’t say it is ‘clear and fine’. But it is certainly not ‘cold and icy’. So, for what it is worth, we are in for some cold weather.

Candlemas – the Last day of medieval Christmas and the Lords of Misrule.

It’s also the official end of all things Christmas. For most of us Christmas decorations were supposed to be pulled down on January 5th, but, the Church itself puts an end to Christmas officially at Candlemas so Cribs and Nativity tableaux need to be removed today.

John Stow, in the 16th Century describes the period between Halloween and Candlemas as the time when London was ruled by various Lords of Misrule and Boy Bishops (see my post here). In the piece below, Stow also talks about a terrible storm that took place in February 1444.

Against the feast of Christmas every man’s house, as also the parish churches, were decked with holm, ivy, bays, and whatsoever the season of the year afforded to be green. The conduits and standards in the streets were likewise garnished; amongst the which I read, in the year 1444, that by tempest of thunder and lightning, on the 1st of February, at night, Powle’s steeple was fired, but with great labour quenched; and towards the morning of Candlemas day, at the Leaden hall in Cornhill, a standard of tree being set up in midst of the pavement, fast in the ground, nailed full of holm and ivy, for disport of Christmas to the people, was torn up, and cast down by the malignant spirit (as was thought), and the stones of the pavement all about were cast in the streets, and into divers houses, so that the people were sore aghast of the great tempests.’

Robert Herrick has a 17th Century poem about Candlemas:

Ceremony Upon Candlemas Eve

Down with the rosemary, and so

https://www.catholicculture.org

Down with the bays and misletoe;

Down with the holly, ivy, all

Wherewith ye dress’d the Christmas hall;

That so the superstitious find

No one least branch there left behind;

For look, how many leaves there be

Neglected there, maids, trust to me,

So many goblins you shall see.

On This Day

1602 – Twelfth Night by William Shakespeare performed for the first time.

This play was commissioned by the Lawyers of Middle Temple, in Fleet Street London for the end of the Christmas Season. It was written by Shakespeare and first performed in Middle Temple Hall which is still standing. For the folklore of Twelfth Night see my post here.

1880 – First shipment of frozen meat arrives in London from Australia. It was in excellent condition despite a leaving Melbourne in Dec 1879. Hay’s Gallerie in London was one of the world’s first warehouses with refrigeration.

1943 – German Army surrenders ending the Battle of Stalingrad, marking the beginning of the end of the WW2.

Today is Groundhog Day in the USA. This is when the groundhog comes out to see what the weather is like. If it is dull and wet he stays up because winter will be soon over, if it is sunny and bright he goes back to his burrow to hibernate for another 6 weeks. Originally, a German custom associated with the badger. A groundhog is a woodchuck which is a marmot. Does this workas a forecast method? Not being in America I don’t know but what I do know is:

How much wood could a woodchuck chuck

If a woodchuck could chuck wood?

As much wood as a woodchuck could chuck,

If a woodchuck could chuck wood.

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/42904/how-much-wood-could-a-woodchuck-chuck-

First published 2022, revised 2023, 2024, 2025 On This day added February 2026

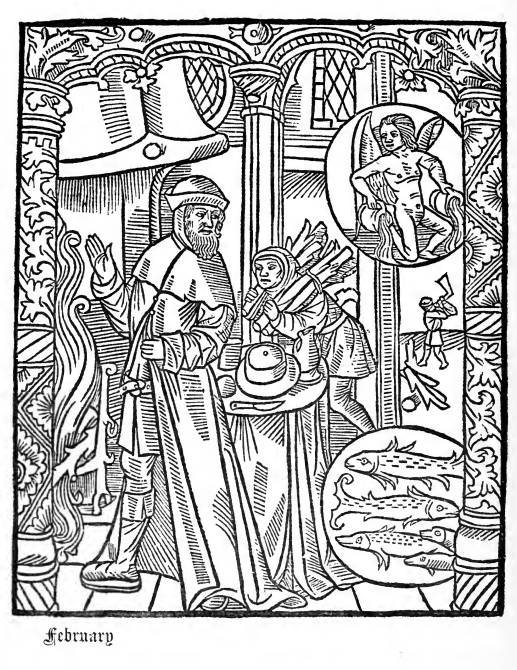

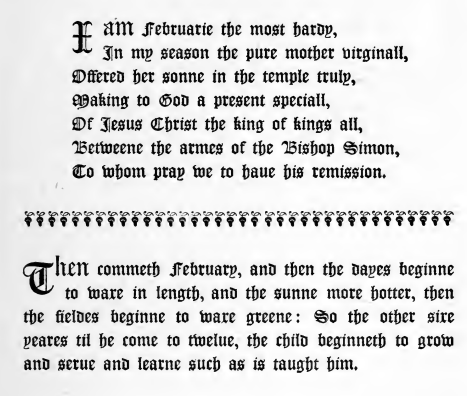

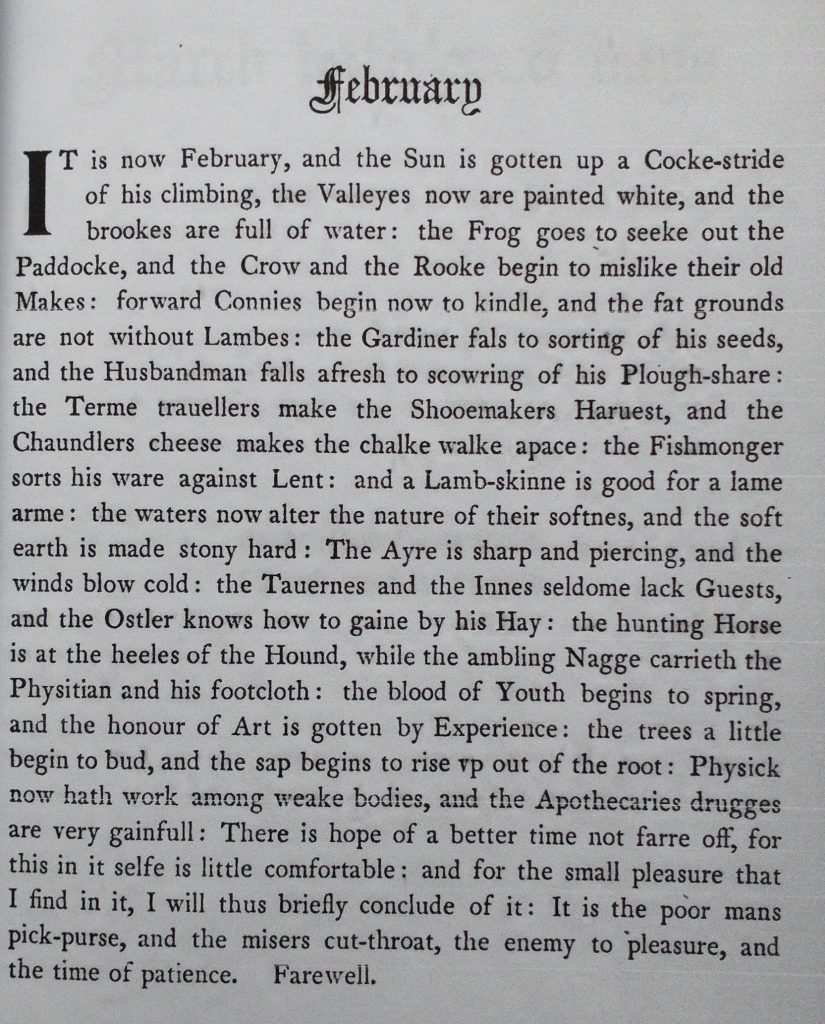

February – ‘the enemy to pleasure and the time of patience’

The 15th Century French illustration, above, shows February as a time to cut firewood, dress warmly and stay by the fire. Food on the table is a nutritious pie and the fish are there to remind us it is the month of Pisces. In the other roundel is the other February star sign the Water Carrier, Aquarius.

The poem above is a reference to the Candlemas celebration of the presentation of the child Jesus at the Temple. The paragraph below the line (above) gives a summary of February. It ends with the idea that runs through the Kalendar. There are twelve apostles, twelve days of Christmas, twelve months in the year. So, there are twelve blocks of six years in a person’s allotted 72 years of life. In the January entry the Kalendar suggests the essential uselessness of 0-6 year old children. But for February, it allows that 6-12 years old children are beginning to ‘serve and learn’.

The Kalendar’s View of February

Below, is the text for February. This gives a rural view of life in winter. It ends with the line that February:

‘is the poor man’s pick-purse, the miser’s cut-throat, the enemy to pleasure and the time of patience.’

About the Kalendar of Shepherds.

The Kalendar was printed in 1493 in Paris and provided ‘Devices for the 12 Months.’ The version I’m using is a modern (1908) reconstruction of it. It uses wood cuts from the original 15th Century version and adds various texts from 16th and 17th Century sources. (Couplets by Tusser ‘Five Hundred Parts of Good Husbandrie 1599. Text descriptions of the month from Nicholas Breton’s ‘Fantasticks of 1626.) This provides an interesting view of what was going on in the countryside every month.

For more on the Kalendar look at my post here.

The original Kalendar can be read here: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/f4824s6t

Hesiod and February

Hesiod, in his ‘Works and Days’ describes February as a merciless cold, windy time. Hesiod was writing around 700BC. He gave us ‘the story of Prometheus and Pandora, and the so-called Myth of Five Ages.’ (Links are to Wikipedia.)

Avoid the month Lenaeon, (February) wretched days, all of them fit to skin an ox, and the frosts which are cruel when Boreas blows over the earth.

He blows across horse-breeding Thrace upon the wide sea and stirs it up, while earth and the forest howl.

On many a high-leafed oak and thick pine he falls and brings them to the bounteous earth in mountain glens: then all the immense wood roars and the beasts shudder and put their tails between their legs, even those whose hide is covered with fur; for with his bitter blast he blows even through them, although they are shaggy-breasted.

He goes even through an ox’s hide; it does not stop him. Also he blows through the goat’s fine hair.

But through the fleeces of sheep because their wool is abundant, the keen wind Boreas pierces not at all; but it makes the old man curved as a wheel.

And it does not blow through the tender maiden who stays indoors with her dear mother, unlearned as yet in the works of golden Aphrodite, and who washes her soft body and anoints herself with oil and lies down in an inner room within the house,

on a winter’s day when the Boneless One (an Octopus or a cuttle?) gnaws his foot in his fireless house and wretched home; for the sun shows him no pastures to make for, but goes to and fro over the land and city of dusky men, and shines more sluggishly upon the whole race of the Hellenes.

Then the horned and unhorned denizens of the wood,] with teeth chattering pitifully, flee through the copses and glades, and all, as they seek shelter, have this one care, to gain thick coverts or some hollow rock.

Then, like the Three-legged One (an old man with a stick) whose back is broken and whose head looks down upon the ground, like him, I say, they wander to escape the white snow.

Original text available here. and for more on Hesiod see my post here.

Februarius

The Roman month Februarius was the month of purification. Februa was the name of the purification ritual held on February 15 (full moon) in the old lunar Roman calendar. The Romans originally considered winter a monthless period of the year. So they only had 10 months to the year. Later they added January and February. March was the first month, so September was the 7th month, October the 8th, November 9th and December the 10th and final month. Names derived from the Latin for 7th, 8th, 9th, 10th.

For more on the Roman Calendar look at my posts

https://chr.org.uk/anddidthosefeet/march-1st-the-month-of-new-life/

https://chr.org.uk/anddidthosefeet/leap-day-february-29th/

First Published February 4th 2024, revised 2025, 2026

Annual Grimaldi Memorial Service, All Saints, Haggerston. First Sunday in February

Today, was the Annual Grimaldi Memorial Service in Haggerston, Hackney, London. It began as a memorial service for the famous Regency Clown Joseph Grimaldi. But it has become a service to celebrate Clowns. The service takes place on the first Sunday in February. The service used to be at Holy Trinity Church, but has switched to Haggerston.

Joseph Grimaldi

Grimaldi was born on 18 December 1778. He died in poverty on 31 May 1837. In between, he was the most famous clown. He transformed the Harlequin role and made the white-faced clown the central part of the British Pantomime. The part became known as a Joey after Grimaldi. He performed at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, the Sadler’s Wells and Covent Garden theatres.

All Saints Church, Haggerston

All Saints Church, Haggerston is 5 minutes walk from where I live and 2 minutes from where my Dad was born. (see my post here). So I popped in today and took this video. The service, which has been held since the 1940s, attracts clown performers from all over the world who attend the service in full clown costume. The Spitalfield’s Life blog has a very full description of the service, and lots of very good pictures. Follow the link below:

First Published February 1st 2026

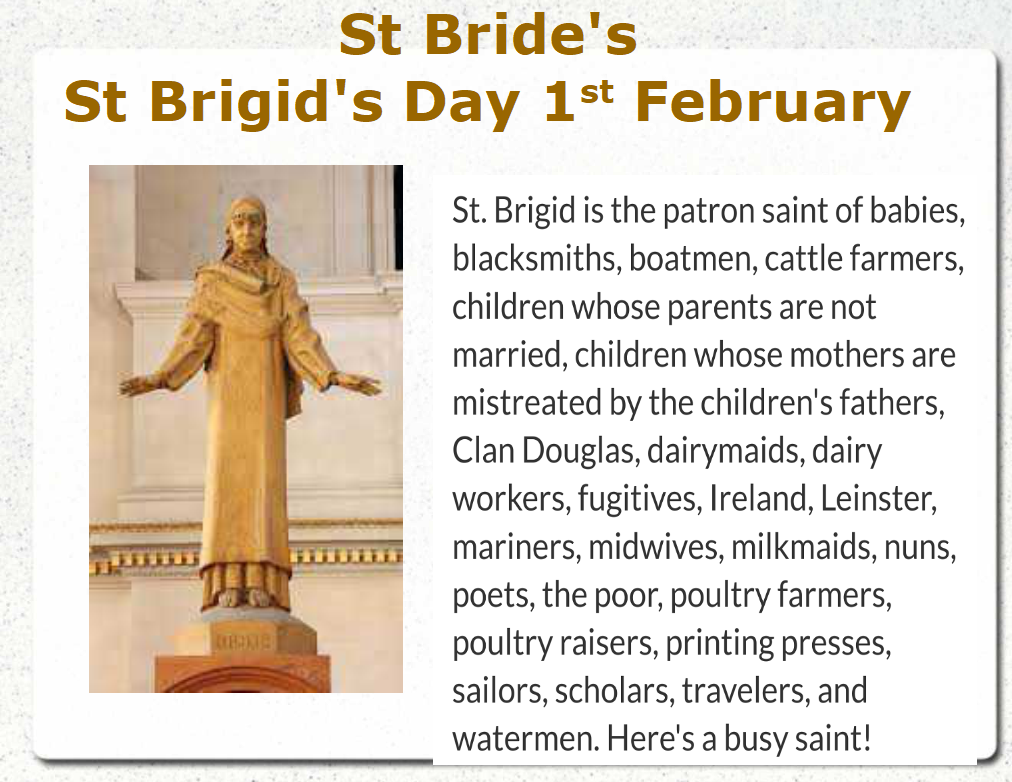

Festival of Imbolc, St. Bridget’s Day February 1st

Imbolc and St Bridget’s Day

Today is Imbolc, one of the four Celtic Fire Festivals. It corresponds with St Bridget’s Day, which is a Christian festival for the Irish Saint, and is the eve of Candlemas. Bridget is the patron saint of all things to do with brides, marriage, fertility, and midwifery (amongst many other things, see below). And in Ireland, 2026 was the third St Bridget’s/ Imbolc Day Bank Holiday.

St Bridget, aka Briddy or Bride, converted the Irish to Christianity along with St Patrick in the 5th Century AD. Despite being a Christian, she appears to have taken on the attributes of a Celtic fertility Goddess. Her name was Brigantia, and it is difficult to disentangle the real person from the myth.

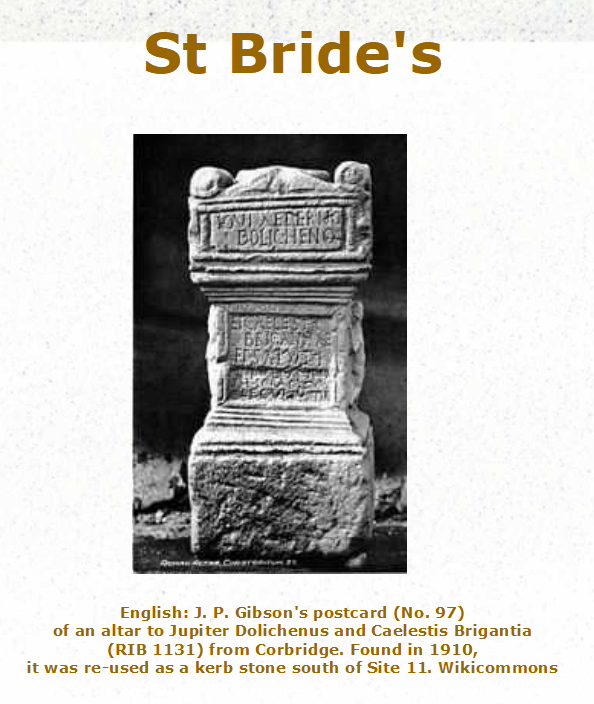

Brigantia

Archaeologists have found various Roman altars dedicated to Brigantia. The Brigantes tribe in the North are named after the Goddess (probably). They were on the front line against the invading Romans in the 1st Century AD, and led by Queen Cartimandua. The Queen tried to keep her tribe’s independence by cooperating with the Romans. A few years later, Boudica took the opposite strategy. But both women had executive power as leaders of their tribes. This suggests a very different attitude to woman to the misogyny of the Romans.

Wells dedicated to St Bridget

St Bride is honoured by many wells dedicated to her. Often they are associated with rituals and dances concerned with fertility and healthy babies. And perhaps, the most famous, was near Fleet Street. This was Bridewell, which became the name of Henry VIII’s Palace, and later converted into an infamous prison. St Bride’s Church, built near to the Well, has long been a candidate as an early Christian Church. Sadly, the post World War Two excavations found nothing to suggest an early Church. But, they did find an early well near the site of the later altar of the Church, and remains of a Roman building, possibly a mausoleum. Perhaps the Church may have been built on the site of an ancient, arguably holy, well. However, this is only a guess.

The steeple of St Brides is the origin of the tiered Wedding Cake, which, in 1812, inspired a local baker to bake for his daughter’s wedding.

February signs of life

Imbolc and St Bridget’s Day are the time to celebrate the return of fertility to the earth as spring approaches. In my garden and my local park, the first snowdrops are out. Below the bare earth, there is a frenzy of bulbs and seeds budding, and beginning to poke their shoots up above the earth, ready for the Spring. In the meadows, ewes are lactating, and the first lambs are being born.

Violets, bulbs, and my first Daffodil of the year. Hackney (2022), London by K Flude

And let’s end with the Saint Brigid Hearth Keeper Prayer Courtesy of SaintBrigids.org

Brigid of the Mantle, encompass us,

Lady of the Lambs, protect us,

Keeper of the Hearth, kindle us.

Beneath your mantle, gather us,

And restore us to memory.

Mothers of our mother, Foremothers strong.

Guide our hands in yours,

Remind us how to kindle the hearth.

To keep it bright, to preserve the flame.

Your hands upon ours, Our hands within yours,

To kindle the light, Both day and night.

The Mantle of Brigid about us,

The Memory of Brigid within us,

The Protection of Brigid keeping us

From harm, from ignorance, from heartlessness.

This day and night,

From dawn till dark, From dark till dawn.

For more about go to this webpage St Bridget. To read my post on Mary Musgrove’s Candlemas Letter in Jane Austen’s Persuasion follow this link.

Imbolc and Myths and Legends Walks

I give walks about Imbolc and other Celtic festivals, and at May Eve, the Solstices, Equinoxes, Halloween and Christmas (when I have time). You might like to attend these walks or virtual tours. The following are currently in my calendar. I will be adding other walks to the calendar as the year progresses.

The Spring Equinox London Virtual Tour 7.30pm Fri 20th March26 To book

The London Equinox and Solstice Walk 2:30pm Sat 21st March26 To book

For more of my walks see the walks page of this blog here: https://www.chr.org.uk/anddidthosefeet/walks

First published in 2023, revised and republished Feb 2024, 2025, 2026

British Exceptionalism Brexit Day January 31st

Today is the Anniversary of the day Britain left the European Union in 2020. It is possible to argue the case that one of the reasons so many people were willing to vote to leave the Union was English or British Exceptionalism. I think most people would be thinking of Winston Churchill and World War 2, and the British Empire. But you can argue a case that there has long been important distinctions between Britain and Europe.

I find it amusing that we left Europe at 11pm on January 31st 2020, which was midnight in the European Union. See the BBC round up on Britain and Europe.

This Island Story

When I was at school, there was a lot of emphasis on Great Britain being an Island. This is rarely emphasised in the 21st Century. But it was part of the Imperial story of the British Empire and helped distance ourselves from ‘the Continent’.

That Island story didn’t begin until the Mesolithic period. Before that, Britain was physically part of Europe, and the Thames was but a tributary of the Rhine. Then the land bridge that is now called Doggerland was swept away by rising meltwater. By 8,000 years BP. Britain was an Island.

Around 4000BC, the so-called Neolithic Revolution spread farming throughout Europe. But, the Channel acted as a barrier. So, it took an extra hundred years or so for farming to begin to penetrate Britain. The early farmers brought with them not only the domestic animals, crops, pottery and ground axes but also a new form of housing consisting of long, rectangular wooden houses. The DNA of the people of Britain, was radically changed and the so-called Western Neolithic DNA mostly took over. Strangely, the long house did not survive very long as a popular design. Britain while accepting the new farming technology, seem to have reverted to their own form of housing

Post Roman divergence?

While most major style and technology changes over the next 4 millenia were shared with Europe, Britain often had its own versions. Britain shared with Europe the adoption of the Celtic Languages and eventual integration into the Roman Empire. But, when the western part of the Roman Empire fell in the 5th Century, Britain had a different experience to much of Europe. On the face of it, a similar sequence happened. The Western Empire was taken over by Germanic Kings. The Franks in France and Germany; the Anglo Saxons in England; the Lombards in Italy and Goths, Visigoths, Vandals in Spain (and N. Africa). A similar sequence on the surface.

But on the mainland the German Kings allowed the local cultures to continue and adopted the Latin language, and Christian religion as their own. They maintained a strong tradition of Roman law and culture. French, Italian, Spanish, Rumanian are all romance languages based on Latin.

But across the Channel to England, it was different. Our German Kings didn’t adopt the Latin language and the native Celtic dialects died out (except of course in Cornwall, Wales, Scotland and Ireland ), They also maintained their pagan beliefs. So English culture is Germanic and not Roman. We do not have a foundation in Latin culture and Roman law. This is very different to western Europe.

Napoleon founder of modern Western Europe

Of course the Anglo-Saxons eventually soon adopted Christianity. In the 16th Century Britain turned against the universal Catholic Church. This was a rupture that had a similar impact to Brexit. But the next really significant difference was the changes instituted by Napoleon. He subdued then rationalised and liberalised the continent. He had dreams of a United Europe of Nations (in contrast to the Empires that held sway (such as the Holy Roman Empire, and the Austro-Hungarian Empirehttps://www.napoleon-series.org/research/napoleon/c_unification).

Most legal systems in Europe are based on Roman Law as amended by the Napoleonic code. England by contrast is based on the Common Law.

So these differences combined with our arrogance derived from Empire, the Industrial Revolution and belief we won World War 2. And our cultural pride based on our perception of the preeminence of people such as Shakespeare, Newton and Darwin etc etc). All this probably lay behind ‘British Exceptionalism’. This helped a nationalistic and misguided belief that we are held back by Europe despite all the evidence to the contrary.

And the future?

Opinion polls make it clear that most people think Brexit was a mistake, and they blame it on the Conservatives, Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage. Economists are clear the damage it has done to Britain’s financial position. And yet the main parties have been very reluctant to consider a return to Europe. Instead, Sunak and Starmer have tried to sort problems out on a case by case basis, without suggesting we go back into the European Union.

However, there is a dawning awareness that Europe cannot depend upon the US playing its usual leading role in maintaining the international status quo, and this may accelerate our move back towards Europe. Canadian Prime Minster Carney is proposed the formation of an alternative economic alliance to replace dependence on the US, and this may be our route back into the European Single Market.

Advice for Lambs

From ‘ FIUE HUNDRED POINTES OF GOOD HUSBANDRIE. BY THOMAS TUSSER.

The Edition of 1580 collated with those of 1573 and 1577.

¶ Januaries husbandrie.

Yoong broome or good pasture thy ewes doo require,warme barth and in safetie their lambes doo desire.Looke often well to them, for foxes and dogs,for pits and for brembles, for vermin and hogs.

More daintie the lambe, the more woorth to be sold, the sooner the better for eaw that is old. But if ye doo minde to haue milke of the dame, till Maie doo not seuer the lambe fro the same.

Ewes yeerly by twinning rich maisters doo make, the lamb of such twinners for breeders go take. For twinlings be twiggers, encrease for to bring, though som for their twigging Peccantem may sing.

Note ewes who had twin lambs were thought to be better and fetched more at market. They were called twinlings.

On This Day

1606 – Guy Fawkes and fellow conspirators are hanged, drawn and quartered for plotting to blow up Parliament and King James. See my post on the Gunpowder Plot.

1865 – Congress passes the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, abolishing slavery.

1953 – The North Sea Flood assail the east coast of Britain killing 280 people. ‘The combination of wind, high tide, and low pressure caused the sea to flood land up to 5.6 metres (18 ft 4 in) above mean sea level.’ (Wikipedia).

Deutsch: Sturmflut von 1953 Date 25 September 2008 Source: Draco. GNU Free Documentation License

You might like to see some great pictures of the floods here.

First Published 2025, revised and OnThis Day added 2026

The Martyrdom of Charles I & ‘Get Back’ January 30th

January 30th is the anniversary of the execution of King Charles I. Today, he was beheaded as a murderer and traitor. Or as a Royalist would see it, it is the anniversary of the Martyrdom of Charles I.

Thousands came to see the execution, amongst them Samuel Pepys. They crowded around the scaffold outside a window of Inigo Jones’s magnificent Banqueting Hall, in Whitehall, London. Charles was brought into the Banqueting House. There he must have looked up at the magnificent Peter Paul Reubens’ ceiling. Charles had commissioned the painting to depict of the Apotheosis of his father, James I. It was the symbol of the Divine Right of the King to rule.

Scaffold to Heaven?

I doubt he saw the irony. I suspect he thought he was going to heaven to join his father, in glory as a Martyr to his religion. He walked outside, through the window, into the cold January air. Two of his bloodstained shirts still exist, probably to stop him shivering. He wanted to be seen as going fearless to his death not shivering with fear. Then, he made a short speech exonerating himself. He spoke without stammering for the first time in his public life. The Rooftops around were lined with spectators. Black cloth framed the scaffold. As the executioner axe fell, there was a dull grown from the crowd (most could not see the axe falling).

This was on January 30th, 1648. But, if you look at a history book, it will tell you it was in 1649. This was before our conversation to the Gregorian calendar. Then the year number changed not as we do on January 1st but on March 25th. This was the day the Archangel Gabriel revealed to the Virgin Mary that she was pregnant. For more on the importance of March 25th look at my Almanac entry here:

‘Oh the stupendous, and inscrutable Judgements of God’

On the same day, twelve years later, in 1661 Oliver Cromwell and his chief henchmen were dug up from their splendid Westminster Abbey tombs. Their bodies were abused by official command. Cromwell’s head was stuck on the top of Westminster Hall. There it remained until blown off in the Great Fire of 1703 (or 1672, or 1684). Then, it taken to Cambridge, Sidney Sussex College, which Cromwell attended. Only the Head Porter knew where. (According to someone who came on my Oliver Cromwell Walk last year.) Whether it is his head or not is disputed. The tale of the head is told in detail here.

The Royalist, John Evelyn, said in his diary:

This day (oh the stupendous, and inscrutable Judgements of God) were the Carkasses of that arch-rebel Cromwel1, Bradshaw, the Judge who condemned his Majestie and Ireton, sonn in law to the usurper, dragged out of their superb Tombs (in Westminster among the Kings) to Tybourne, and hanged on the Gallows there from 9 in the morning till 6 at night, and then buried under that fatal and ignominious Monument in a deep pit. Thousands of people (who had seen them in all their pride and pompous insults) being spectators .

Samuel Pepys records by contrast:

…do trouble me that a man of so great courage as he was should have that dishonour, though otherwise he might deserve it enough…

Pepys served the Parliamentary side before the restoration of Charles II, when he adroitly, swapped over to the Royalist side.

Every year, I do a Guided Walk and a Virtual Tour on Charles I and the Civil War on this day or the last Sunday in January. Look here for details.

On This Day

1661 – Oliver Cromwell’s corpse disinterred and ritually executed

1826 – The Menai Suspension Bridge, considered the world’s first modern suspension bridge, Architect Thomas Telford

1933 – Hitler appointed Chancellor of Germany

1969 – Get Back to Where you Once Belonged – the anniversary of the rooftop concert in Saville Row where the Beatles played ‘Get Back’.

First published in 2023, revised on January 29th 2024,2025, 2026

Pax, the Concordia Peace Festival, Elagabalus, and Carausius January 29th

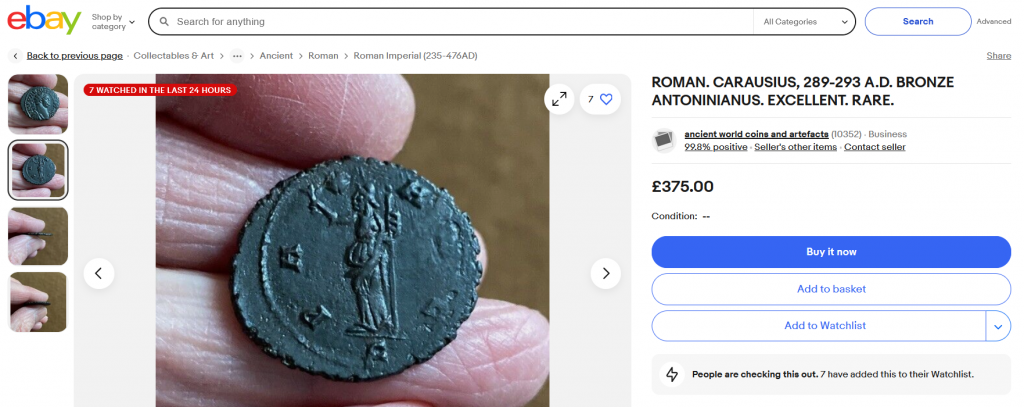

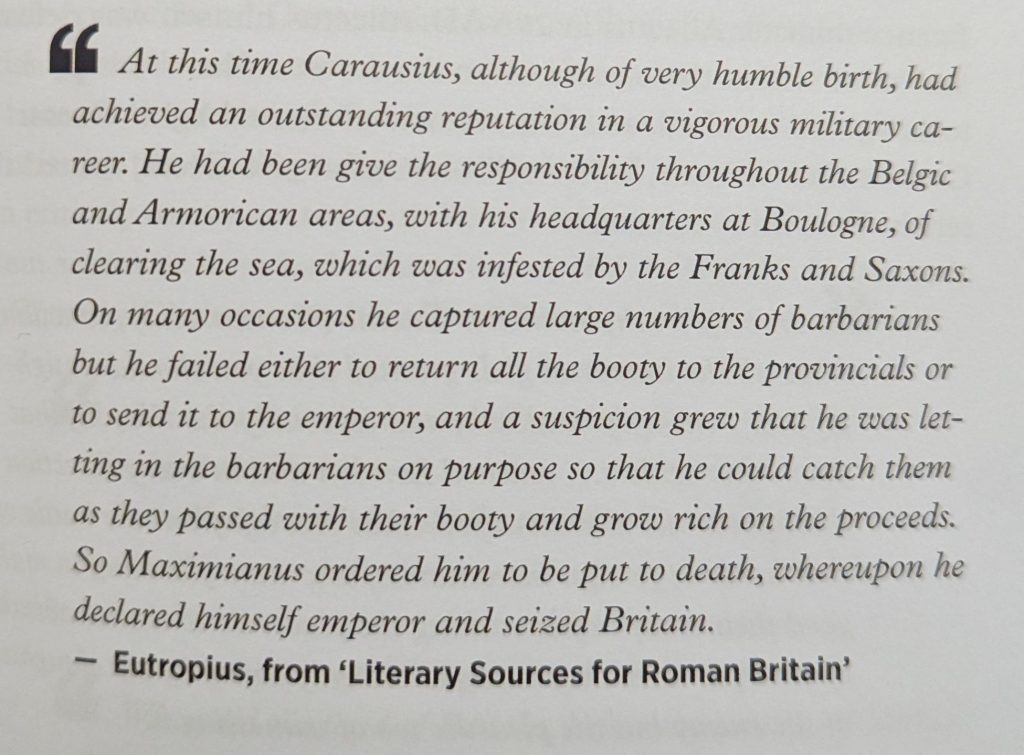

The Goddess Book of Days (Diane Stein) lists today as the birthday of Pax and her Greek equivalent Irene. She is the Goddess of Peace and the daughter of Jupiter and the Justitia, Goddess of Justice. This suggests that a lasting peace can only be assured by strength and justice. The usurping Emperor Carausius (whose coin you can see above) had good reason to use Pax on his coins. He took control of Britain and some of Gaul from the Roman Empire. But he hoped he might rule alongside the Tetrachy of Emperors set up by Diocletian.

This is what Eutropius wrote:

He was murdered by Allectus, his financial minister in 296AD. Text above taken from my book In Their Own Words where you can read the rest of Carausius’ story.

Concordia

The Goddess book also says this is the day of the Concordia Peace Festival in Rome. Concordia is the Goddess of agreement, in war, marriage and in civic society. Harmonia is the Greek equivalent. Ovid has special days to Concordia on January 17th and January 30th. I’m led to the idea that much of January was dedicated to Concordia and Pax. For more on Concordia, look at my January 17th post here.

Pax in Ovid

Pax had her festival on the 30th January. Ovid in Fasti writes:

Book I: January 30

My song has led to the altar of Peace itself.

This day is the second from the month’s end.

Come, Peace, your graceful tresses wreathed

With laurel of Actium: stay gently in this world.

While we lack enemies, or cause for triumphs:

You’ll be a greater glory to our leaders than war.

May the soldier be armed to defend against arms,

And the trumpet blare only for processions.

May the world far and near fear the sons of Aeneas,

And let any land that feared Rome too little, love her.

Priests, add incense to the peaceful flames,

Let a shining sacrifice fall, brow wet with wine,

And ask the gods who favour pious prayer

That the house that brings peace, may so endure.

Now the first part of my labour is complete,

And as its month ends, so does this book.

Translated by A. S. Kline 2004 (Tony has a lovely site here: where he makes his translations freely available.)

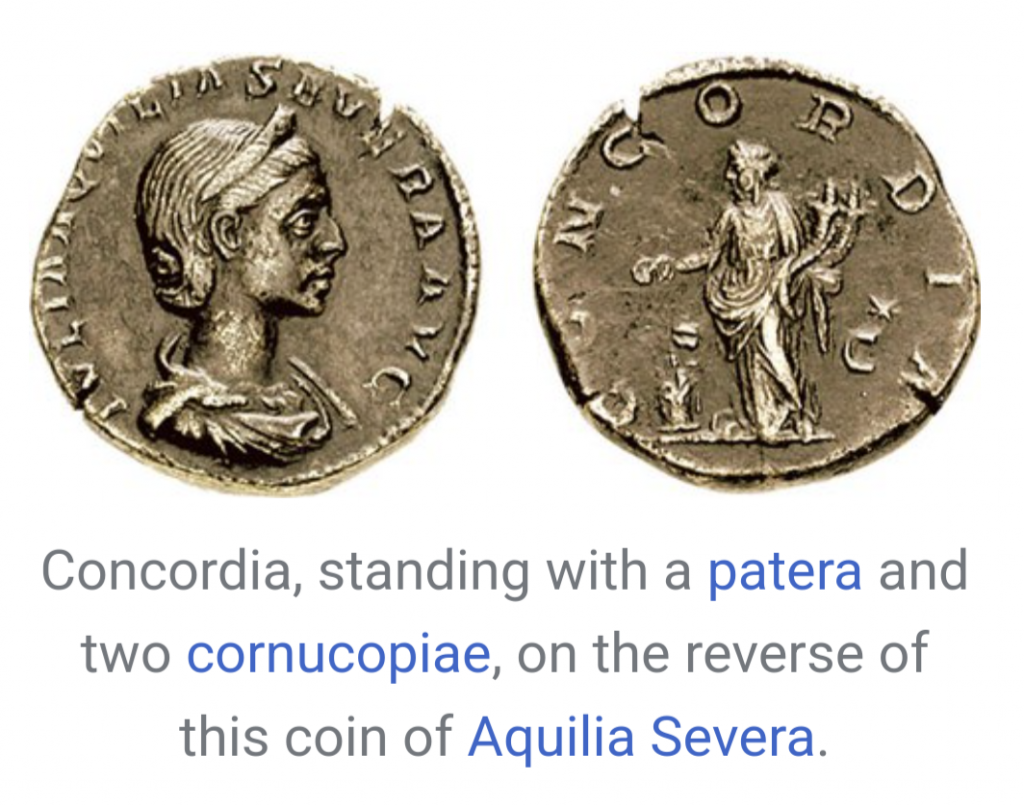

Concordia, Julia Aquilia Severa & Elagabalus

The coin above is of Empress Julia Aquilia Severa. She was a vestal virgin, who married the Emperor Elagabalus (c. 204 – 11/12 March 222). She was his 2nd and 4th wife. Normally, the punishment for a vestal Virgin losing their virginity was to be buried alive.

The Trouble with Pronouns

But I could have said ‘her 2nd and 4th wife’. Some sources suggest Elgabalus wanted to be known as a woman. The Wikipedia page of his wife has Elagabalus with the pronoun, ‘Her’. While the Emperor’s own web page uses ‘him’ throughout. He or she married several women. And also married to several men. They were also accused of prostituting himself in Taverns and Brothels. Clear? Confusing pronouns? Sorry to hedge my bets, but we don’t know what Elagabalus would want us to use? Wikipedia says:

‘In November 2023, the North Hertfordshire Museum in Hitchin, United Kingdom, announced that Elagabalus would be considered as transgender and hence referred to with female pronouns in its exhibits due to claims that the emperor had said “call me not Lord, for I am a Lady”‘

Elagabalus was born Sextus Varius Avitus Bassianus. He adopted the name of Elagabalus as he was a supporter of the Syrian Sun God Elagabal. He, a Syrian, wanted to promote the God to the top of the Roman Pantheon of Gods. Elagabalus rose to power partly because of his strong Grandmother, Julia Maesa. She was the sister of Julia Domna, the wife of African Emperor Septimus Severus (who lived for some time in York). Their children are the Emperors in Gladiator II starring Paul Mescal. Caracalla was Elagabalus’s cousin.

Elagabalus’s reign was fairly chaotic. He lost power, when his Grandmother transferred support to his cousin, Alexander. Elagabalus and his mother were assassinated.

Here, is a fascinating article in the Guardian about the Pax Romana. ‘Their heads were nailed to trees.’

Pax & Tagging

Posh boys in England, playing tagging games, used to shout ‘Pax’ to claim immunity or to call a temporary halt in the contest. I remember my childhood friends using the word ‘vainites’ as well as pax. But we were not by any means posh. There are many other ‘truce’ terms in tagging games. See them in this fascinating. Wikipedia page. From which I discover that Vainites comes from the medieval period and means: ‘to make excuses, hang back or back out of battle’.

First Published in January 2024, and revised, expanded and retitled in January 2025. Republished 2026

Gilbert White & The Cold of January 1776 January 28th

January 1776:

‘On the 27th much snow fell all day, and in the evening the frost became very intense. At South Lambeth, for the four following nights, the thermometer fell to 7, 6, 6, and at Selborne to 7, 6, 10, and on the 3ist of January , just before sunrise, with rime on the trees and on the tube of the glass, the quicksilver sunk exactly to zero, being 32 degrees below the freezing point’ Gilbert White

Gilbert White and Darwin

He, of course, is talking Fahrenheit, so well below zero. If there was a Giant upon whose shoulders Charles Darwin climbed, then Gilbert White owned one pair.. He was one of many churchmen of the 18th and 19th Century who spent their extensive leisure time, on observing God’s wonderful creation in their gardens and parishes. What made White so important was that his practice was ‘observing narrowly’ and regularly. For example, his observations of the importance of earth worms were fundamental to Charles Darwin’s own studies. When Darwin came back from his travels on the Beagle, he settled in a country property in Orpington. Like White, he used his garden and the local area as his laboratory. Here he worked to prove his theory of evolution.

Gilbert White and Earth worms

Earth worms were one of Darwin’s passions. This is what Gilbert White wrote about their contribution to nature:

“Earth-worms, though in appearance a small and despicable link in the chain of Nature, yet, if lost, would make a lamentable chasm. For, to say nothing of half the birds, and some quadrupeds which are almost entirely supported by them, worms seem to be the great promoters of vegetation, by boring, perforating, and loosening the soil, and rendering it pervious to rains and the fibres of plants, and, most of all, by throwing up such infinite numbers of lumps of earth called worm-casts, which, being their excrement, is a fine manure for grain and grass.”

(Quoted from https://gilbertwhiteshouse.org.uk)

By such minute and repeated observations, Gilbert White investigated the food chain, and the migration of birds (which was at the time disputed). He laid the foundations of what we now call ecology.

Gilbert White’s Career

He became Dean of Oriel College in Oxford. But chose to spend his career in the relatively humble occupation of Curate. A Curate is the bottom-feeder in the Anglican Church food chain. A Curate hardly earned enough to maintain a position in the Gentry (£50 p.a.). Although, White was upgraded to the title of Perpetual Curate. He still would only be pulling in, I guess, something like £200 p.a. (Patrick Bronte was also a Perpetual Curate). Essentially, it is Vicar looking after a part of a too large Parish.

Financially, White didn’t need much, he inherited his father’s property at Shelborne, Hampshire. White’s grandfather was the Vicar at Shelborne. But Gilbert could not inherit the title because he went to Oriel College. The ‘living’ of the Parish of Shelborne was ‘in the gift of’ Magdalen College. And they were not going to give the role to an alumnus of a rival college.

Gilbert White & The Austen Family

The house, now open to the public, is just around the corner from Chawton. This is where Jane Austen spent her last years. He was born in 1720; was 55 when Austen was born, and he died in 1793, when she was 18. He lived 4 miles away, so the families knew of each other. We know Jane Austen’s brother wrote a poem about Gilbert White and his natural history observations, particularly on birds.

From ‘Selbourne Hanger’ by James Austen

Who talks of rational delight }

When Selbourne’s Hill appears in sight }

And does not think of Gilbert White? }

Such sure he was – by Nature grac’d

With her best gift of genuine taste;

And Providence – which cast his lot

Within this calm, secluded spot,

Plac’d him where best th’enquiring mind

Might study Nature’s works, and find

Within her ever open book

Beauties which others overlook.

Enthusiast sweet! Your vivid style

The attentive reader can beguile

Through many a page, and still excite

An Interest in what you write!

For whilst observant you describe

The habits of the feathery tribe

Their Loves and Wars – their nest and Song,

We never think the tale too long.

For more information on White and Austen, go to Gilbert White’s House’s web page here:

More Snow!

Here is more of that epic cold January 1776

‘… but by eleven in the morning, though in the shade, it sprang up to I6J,1 — a most unusual degree of cold this for the south of England. During these four nights the cold was so penetrating that it occasioned ice in warm chambers and under beds ; and in the day the wind was so keen that persons of robust constitutions could scarcely endure to face it. The Thames was at once so frozen over both above and below bridge that crowds ran about on the ice. The streets were now strangely encumbered with snow, which crumbled and trod dusty ; and, turning grey, resembled bay-salt : what had fallen on the roofs was so perfectly dry that, from first to last, it lay twenty-six days on the houses in the city ; a longer time than had been remembered by the oldest housekeepers living…..’

‘The consequences of this severity were, that in Hampshire, at the melting of the snow, the wheat looked well, and the turnips came forth little injured. The laurels and laurustines were somewhat damaged, but only in hot aspects. No evergreens were quite destroyed ; and not half the damage sustained that befell in January, 1768. Those laurels that were a little scorched on the south-sides were perfectly untouched on their north-sides. The care taken to shake the snow day by day from the branches seemed greatly to avail the author’s evergreens. A neighbour’s laurel-hedge, in a high situation, and facing to the north, was perfectly green and vigorous ; and the Portugal laurels remained unhurt.’

More Frost!

‘We had steady frost on to the 25th, when the thermometer in the morning was down to 10 with us, and at Newton only to 21. Strong frost continued till the 31st, when some tendency to thaw was observed ; and, by January the 3d, 1785, the thaw was confirmed, and some rain fell.’

Gilbert White’s House is open to the public and also contains a display on Lawrence Oates, who died on Scots Antarctic expedition. For more information look at my post here.

There is another mention of Gilbert White in the Almanac of the Past here.

Foods in Season

Here are food stuffs that are in season now.

Wild Greens: Chickweed, hairy bittercress, dandelion leaves, sow thistle, winter cress

Vegetables: Forced Rhubarb, purple sprouting broccoli, carrots, brussels sprouts, turnips, beetroot, spinach, kale, chard, leeks, Jerusalem artichokes, lettuces, chicory, cauliflowers, cabbages, celeriac, swedes

Herbs: Winter savory, parsley, chervil, coriander, rosemary, bay, sage

Cheeses: Stilton, Lanark Blue

(from the Almanac by Lia Leendertz)

On This Day

1754 – Horace Walpole coined the new word ‘serendipity’ from the ‘Three Princes of Serendip’ fairy tale. The Princes ‘ere always making discoveries, by accidents and sagacity, of things they were not in quest of.’

1898 – Walter Arnold became the first motorist to be fined for speeding. He was going 8 miles an hour in a 2 mile an hour area in Kent

1986 – Explosion of US Space Shuttle Challenger. All 7 astronauts killed, including teacher Christa McAuliffe who would have been the first civilian in space.

The food section posted originally in 2023, the part on Gilbert White written on 28th January 2024, revised 2025, On This Day added 2026

Holocaust Memorial Day & Montaillou January 27th

Statue for Holocaust Memorial Day

The statue commemorates the arrival of Jewish children by train at Liverpool St Station, In London. This was 1938/9 in the Kindertransport. They were sent by parents desperate to save their children from fascist genocide in Germany and Austria. The children were unaccompanied and, as depicted in the statue, stand proud as they arrive in a strange country. They are tagged. And the train track represents both the trains to the death camps, and the train to safety. There are some great photos and more information on the statue in: talkingbeautifulstuff.com

Holocaust Memorial Day and Montaillou

On the subject of prejudice, genocide and abuse of power. I was reminded of one of the formative reads of my life. The great Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie was at dinner at my father-in-law’s house in the 1980s. I was awestruck. Because Montaillou was one of the early histories ‘from below’. The focus was not on kings, queens nor on the flux of states and empires. No, the focus was on the lives (and deaths) of ordinary people. Something that has continued as a focus of my historical interest.

Nor, before Ladurie, had I imagined that medieval lives could be so minutely brought to life. The book was a sensation, selling over a quarter of a million copies. Professor Ladurie became a media star, and, it remains one of the great historical reads. (Of course, the book and the historiography now attracts some criticism, but do read it!)

The context of the story is appalling. In 1208, the Pope decided to launch a crusade against heretics in the South of France. This is about the genocide of the Cathars. The lives of the persecuted are revealed under interrogation by the Cathodic Inquisition. Cathars had many unorthodox and ‘heretical’ ideas. They believed in a Good God and an Evil God. We, humans, are all angels trapped in this terrible world by the Evil God. Women and men were equal and could be reincarnated into each other’s bodies. Our lives are spent awaiting the time we became ‘perfect’ and released to our spiritual form for eternity.

“Kill them all, the Lord will recognise His own”

From the 21st Century, these ideas seem no more nor less irrational than mainstream religions. But these opinions ‘justified’ a Crusade and Inquisition that followed which were truly savage, with many thousand slaughtered. For example, on 22 July 1209, the Catholic forces were led by Arnaud-Amaury. He was not only the Commander of the army but also a Cistercian Abbot. Many of the citizens of Béziers were seeking refuge in St Mary Magdalene. The abbot ordered the doors to be battered down to get at the refugees inside. When asked how the soldiers could separate the Catholics from the Cathars. He replied:

“Caedite eos. Novit enim Dominus qui sunt eius“—”Kill them all, the Lord will recognise His own”.

All 7,000 men, women, and children were killed. Thousands more in the town were mutilated, blinded, dragged behind horses, used for target practice and massacred. Arnaud-Amaury, remember an Abbot, wrote to Pope Innocent III:

“Today your Holiness, twenty thousand heretics were put to the sword, regardless of rank, age, or sex.”

But, despite this savagery in the name of religious purity, reading Montaillou is a pleasure. It brings those persecuted souls back to life in all their human glory.

We are all equally human

The Cathar Crusade is another reminder that it is by intolerance and ‘othering’ of normal homo sapiens which allows the conditions for evil to flourish. Massacres of the innocents becomes possible when sets of people are ‘othered’. Put in a category which, of itself, justifies their treatment. We have a very recent example with the Press Secretary at the White House. She has now referred to US citizens shot by ICE as ‘domestic terrorists’. These statements were made before due consideration of the facts. She may or may not be right, I’m not in a position to be definitive.

But we know that when the Press Secretary made them, no one could know whether she was right, or wrong. She is, in effect, saying: ‘Don’t worry about it. These are bad people who have been killed. No need to look into it too deeply. ‘ (for more on this story look here). We have to treat all human life as equal and sacred. And bring to bear our human empathy before passing judgement. Anything less allows the slaughter of the innocent.

Lessons from the Past

Holocaust Memorial Day offers a chance to remember and it is only by remembering that we can learn from the past. Sadly, more and more school are not marking the day any more. Perhaps as the survivors become fewer? However, other new sources claim that the massacres in Gaza are a cause. This is short-sighted.

Hitler’s rise to power is studied by historians who show how a functioning democracy can be taken down in a series of easy stages. Discrediting new sources, telling lies as if they were fact, subverting the legal system, making use of new media, creating a para-military force not bound by normal restraints. But the one that I think we most need to be aware of is the fact that honest, moral conservatives supported Hitler, despite their qualms about his more extreme policies. It is vital that people speak up before it is too late and too dangerous to oppose the tyranny.

On This Day

Today is also the Roman Festival of Castor and Pollux. (more on the divine twins on my post on the 15th July at the other festival of the Dioscuri).

98 – Trajan succeeds his adoptive Father Nerva

417 – Pope Innocent I declares Pelagius, a British Priest who held opposing views to Augustine of Hippo, excommunicated. For more see my post on Pelagius and Original Sin here.

1606 – The trial of Guy Fawkes and other conspirators begins, ending with their execution on January 31st. See my post on Guy Fawkes and his lantern here.

1880 – Edison received a patent for his electric incandescent lamp.

1945 – Auschwitz & Birkenau Liberated by Soviet Troops

1973 – Vietnam War cease fire came into effect.

First written in January 2023 and revised Jan 2024, 2025,2026