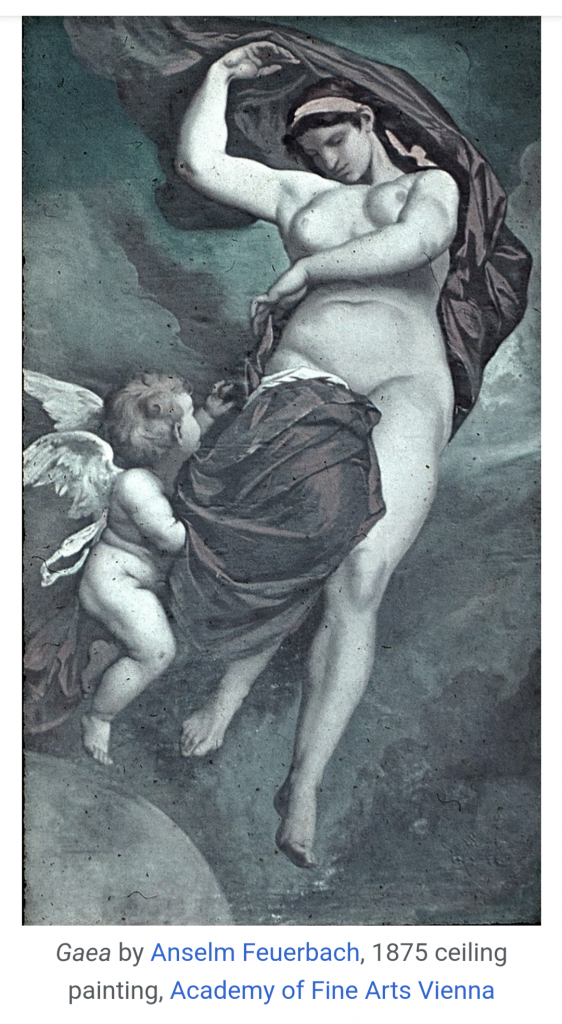

James Lovelock is one of my heroes. He came up with the idea that the Planet Earth is, or can be considered to be, a living being. He named her Gaia, after the Greek Mother Goddess and the mother of all life.

He suggested that the Earth was a self-regulating entity that kept the essentials for life on our planet in balance. Further, he speculated that human activity was putting a strain on the feedback systems that kept the environment sweet for life. Gaia, he suggested, might spit out the cause of the disruption, if we didn’t mend our ways.

Today, a new book on Lovelock was published, and the Guardian ran this lovely article on the contribution of love and Dian Hitchcock to the formation of the theory. Dian and James worked together on the idea when they both worked for Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in California in the 1960’s.

The Many Lives of James Lovelock: Science, Secrets and Gaia Theory, published by Canongate on 12 September and available at guardianbookshop.com

My own take on his theory, is that Gaia keeps the atmosphere and climate within a safe range by a series of feedback loops. Lovelock pointed out that as strains in the system develop, the feedback loops might fracture, readjust and the Earth find a new stable feedback system. This new equilibrium may or may not be compatible with a comfortable environment for humans.

Chris Stringer’s book on the Palaeolithic in Britain is called ‘Homo Britannicus’, shows that during the 900,000 years of genus Homo’s life in Britain, five or so times the climate has changed in these mild islands so it has become inhospitable for humans. He also suggests that there is evidence that the last Ice Age ended fairly swiftly, and that Britain changed from being tundra to a temperate climate perhaps in as little as twenty years. It is only for around 12,000 years that Home Sapiens have lived continuously on these islands.

So, we know climate change is inevitable, and that when it happens it may not be a gradual change. We also cannot be sure it will make the UK warmer because Britain’s temperate climate depends on the warm air of the Gulf Stream and if this is affected Britain may revert to the colder climate of other countries at our latitude like Scandinavia,